After more than a decade of

planning and construction –and watchful attempts at destruction—the most

advanced space telescope in history left the hands of members of Baltimore Local 1501 May 7.

|

| When you have $10 billion and more than decade’s work hanging more than a dozen feet off the ground, you want the IBEW members of Baltimore Local 1501 managing the job.

|

|

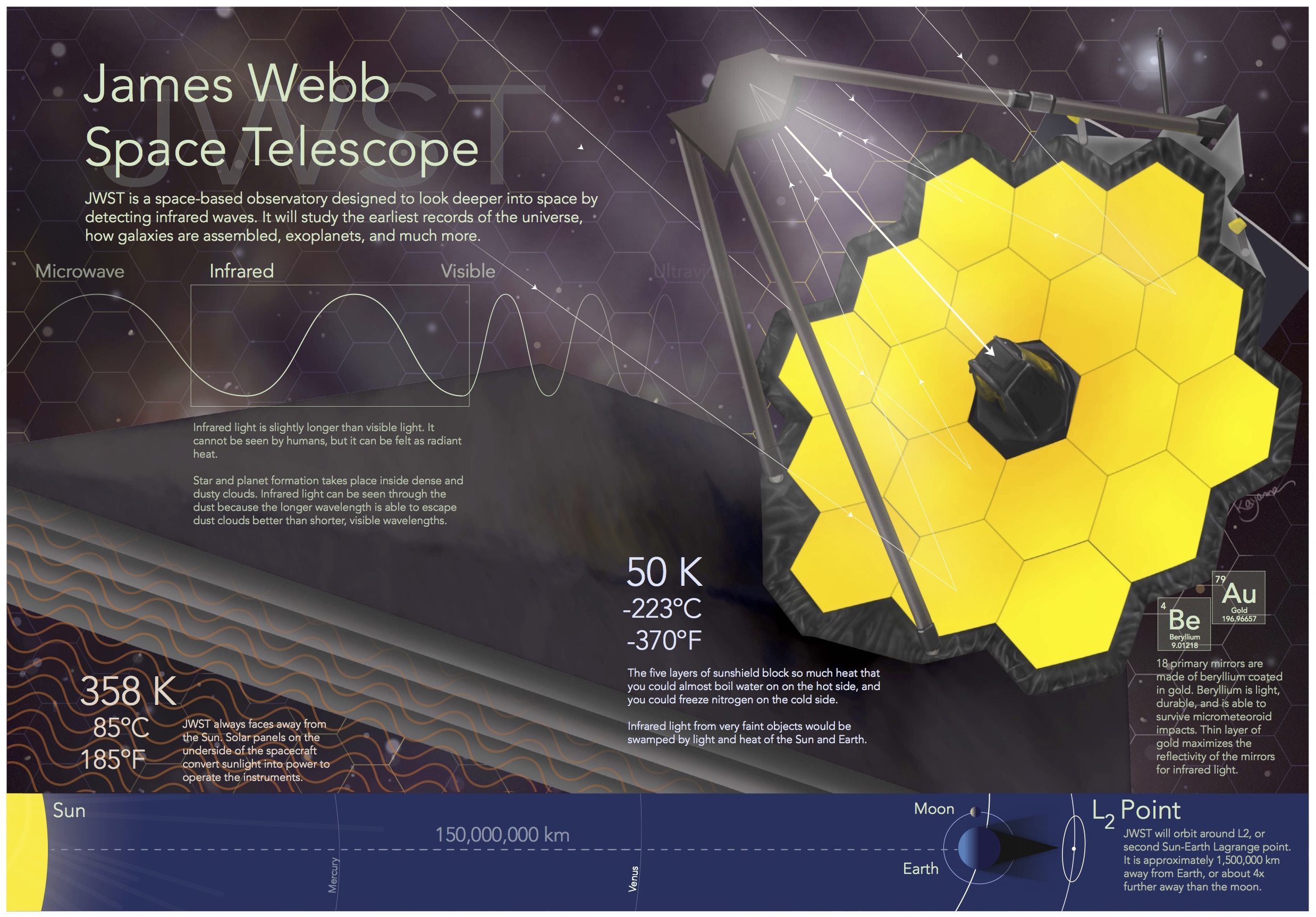

| Members of Baltimore Local 1501 inspect the 18 gold-plated beryllium mirror segments that make up the heart of the most powerful telescope in history, the James Webb Telescope.

|

The James Webb Telescope, left its home at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, for the Johnson Space Center in Houston where it will undergo final preparation for launch, scheduled for October 2018.

The Webb is the successor to the now 20-year-old Hubble telescope, but it is much more than a simple replacement. The Webb telescope is so powerful it can detect just the barest wisps of light that have been traveling through space for nearly 13 billion years from, relatively speaking, moments after the Big Bang, the explosion that created the universe.

The story of the work done by the members of Local 1501 was covered extensively in a 2014 Electrical Worker story (“The Telescope That Will See the First Stars.“)

The key to the Webb’s power to detect light nearly as old as the universe is its 21-foot diameter, gold-plated beryllium mirror and the near absolute-zero temperature of its instruments.

The primary mirror is so large that six of its 18 segments -each nearly the same size as Hubble’s entire mirror-- will hinge backward like a bird folding its wings behind its back to fit into the Ariane-5 rocket that will carry it into space.

|

| The $10 billion telescope has been underway for nearly 20 years and will be able to see some of the faintest and oldest objects in the universe.

|

The temperature requirement is so low that the telescope must be launched more than a million miles away, shaded from the sun by the Earth’s shadow and protected from the heat of the Earth by a five-layer, tennis-court sized heat shield that will unfold in space.

"We only have one chance to get it right," said Delaney Burkhart, mechanical integration specialist, steward and member of Local 1501's executive board. "Our job is to test, and retest and test again until we are confident that one is all we need."

Members of Local 1501 maintained and ran the 12,500 square-foot, nine-story clean room that was home to the Webb and its components and kept it 1,000 times cleaner than an operating room.

Paula Cain and her colleagues in the "blanket shop" handcrafted the multilayered thermal insulation that will protect the parts of the telescope that must stay (relatively) warm from the extremes of space and they will isolate the equipment that must stay extremely cold, safe from the heat of the telescope itself.

Marc Sansebastian designed and built the cooling system's hundreds of small parts, from the gold-plated clamps the size of grains of rice to the cat's cradle suspension system built from wisps of Kevlar thread thinner than a hair.

Engineering technician Nate Allen and his colleagues mounted components of the telescope to hydraulic-driven tables that shake and rattle each piece, froze them in the simulated vacuum of space or blasted them with sound waves generated by ram’s-horn-shaped speakers the size of minivans.

And after trying to rattle everything to pieces, they carefully put everything together so, when the time came, the $10 billion telescope could confidently be sent far beyond where any repair mission could reach it.

"Its purpose is to address the deepest questions we have: Where did we come from? Are we alone?" said Amber Straughn, deputy project scientist at Goddard.

See a simulation of how the Webb will unfold.