After decades of decline, nuclear power is on the verge of a revival in North America.

In the 1960s and ’70s, the U.S. opened an average of three nuclear power plants a year. In 1974 alone, 12 nuclear power plants with 21 reactors came online.

A spider web of red tape, slow permitting, safety hurdles and the wildly changing economics of the energy industry reduced construction to a trickle. Plans for more than 100 reactors died in the ’70s and ’80s. Between 1996 and today, for every new reactor the U.S. built, eight went dark.

Somehow, this always-on, carbon-free energy became a technology of the past.

But power-hungry AI data centers, factories and electric vehicles are finally breaking the dam.

The National Electrical Manufacturers Association released a study predicting 50% growth in electricity demand over the next 25 years driven by a 300% rise in energy consumption by data centers and a 9,000% increase in energy consumption required for EVs. A study from consulting firm McKinsey was even more bullish, predicting 75% growth, from just over 4,000 terawatt-hours to more than 7,000.

“Every energy generation source has a part to play, but the question of the moment is how much of that growth could be filled by a domestic nuclear industry,” said International President Kenneth W. Cooper. “The next decade must be remembered for the North American nuclear renaissance.”

There are signs the rebirth is already here. New reactor designs are leaving labs and starting construction. New, smaller reactors with new fuels and coolants promise lower costs, better safety and shorter construction schedules. IBEW members have been forced by decades of closures to decommission nuclear power plants. Now some are at work bringing them back to life.

In Georgia, IBEW members built two massive reactors at Plant Vogtle, the first newly constructed reactors in the U.S. in 30 years.

In Canada, hundreds of union trades workers, including members of Toronto Local 353, are building a first-of-its-kind small modular reactor power plant.

In Michigan, dozens of members of Kalamazoo Local 131 are recommissioning the shuttered Palisades nuclear power plant. Two more closed reactors, in Pennsylvania and Iowa, are likely to follow.

If all goes according to plan, Kalamazoo, Mich., Local 131 members won’t just be restarting the reactor at Palisades but will also build a series of Holtec SMRs on the same site.

The backers of the next generation of reactors — smaller, simpler, cheaper and safer — have construction and design permits to go with those promises. The IBEW has project labor agreements in place with many of those companies, and boots will be on the ground soon.

There is even optimism for the traditional large nuclear plants. The Trump administration wants 10 more units built by 2030.

“We have about a decade to rebuild a domestic nuclear industry and workforce,” said Utility Department International Representative Matt Warren, a former nuclear power plant worker. “There is unprecedented need globally for reliable, carbon-free power. China is forging ahead. If we fail to develop our own nuclear power supply chain in the next half-decade, we could lose this entire industry like we lost steel and semiconductors.”

Nuclear power’s promise is enormous for the IBEW. Even the new small modular reactors, each one less than 300 MW, would employ hundreds of members for years. Many of the new so-called Gen IV reactor designs can be built off site in factories and delivered in containers, creating an entirely new, potentially IBEW-represented manufacturing supply chain and more business for rail members.

IBEW utility members already operate dozens of nuclear power plants and have contracts to operate many of the new ones.

Recommissioning

The first new nuclear units will likely be old ones brought back to life.

Constellation Energy announced at the end of 2025 that it would restart operation at the Crane Energy Center — better known by its previous name, Three Mile Island.

In Iowa, NextEra announced a partnership with Google parent company Alphabet to reopen the 600-MW Duane Arnold power station, which closed in 2020. The recommissioning is still seeking final approval, but Cedar Rapids Local 405 already has a “handful” of members on site, said Business Manager Matt Resor. Phase II this spring will call for 50 to 60 members, and at peak, Resor expects 200 to 300 tradesman to be at work through 2029.

Far ahead of any of them is the 800-MW Palisades generating station, which closed in 2022 after 51 years. Entergy then sold the plant to decommissioning experts Holtec International. In the past, the company bought retired nuclear plants, including Oyster Creek, Pilgrim and Indian Point, and then made money taking them apart.

Plants Saved From Premature Retirement

Source: Nuclear Energy Institute

Palisades is different. Within months, Holtec applied for a Department of Energy grant to restart the plant and applied to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

In the two years since, between 60 and 80 members of Kalamazoo Local 131 have been doing something that has never been done before: They are turning the plant back on.

“It isn’t a giant job for us, but it is hugely positive. It is largely Book 1 guys, and it’s the highest-paying job in the local,” said Business Manager Jonathan Current.

Nuclear work pays so well because it requires systems and processes unlike any other industry, Warren said.

“There are no interchangeable parts. Every bolt, every nut, every piece has a number and a precise location. There are specific hold points for inspections. If you mess up the radiation check-out procedure, you can slow up a line of 200 people. Working productively in nuclear construction is not easy,” he said.

Certification to work nuclear takes weeks and includes passing background checks. Staffing a nuclear job with badged local members is particularly advantageous at Palisades, because Holtec isn’t planning on stopping with the restart.

The company also announced its intention to build a first-of-its-kind small modular reactor plant using two or more 300-MW reactors.

Current said work clearing land for the SMRs will begin this winter and construction to begin in 2027.

His expectation is that the new reactors will require 200 to 300 electrical workers for five years.

Smaller, Safer & Cheaper

Recommissioning won’t meet anything close to the need for new power generation, however. More than 24 nuclear reactors have shut down in the last 50 years, but once you get past Palisades, Crane in Pennsylvania and Duane Arnold in Iowa, there aren’t many other realistic recommissioning options, Warren said. Indian Point in New York might be on the list, but the real name of the game is new construction.

New construction breaks down into two streams. The first is using the tried-and-tested light water reactors at either the gigawatt scale like Vogtle in Georgia or newer, smaller designs of about 300 MW or less.

The second stream is Gen IV reactors, which not only are smaller than the traditional design at 30 to 500 MW per unit but also use new fuels, coolants and new designs that are incapable of melting down.

The only new nuclear plant currently under construction in North America is a midway point between the traditional and the most exotic Gen IV designs.

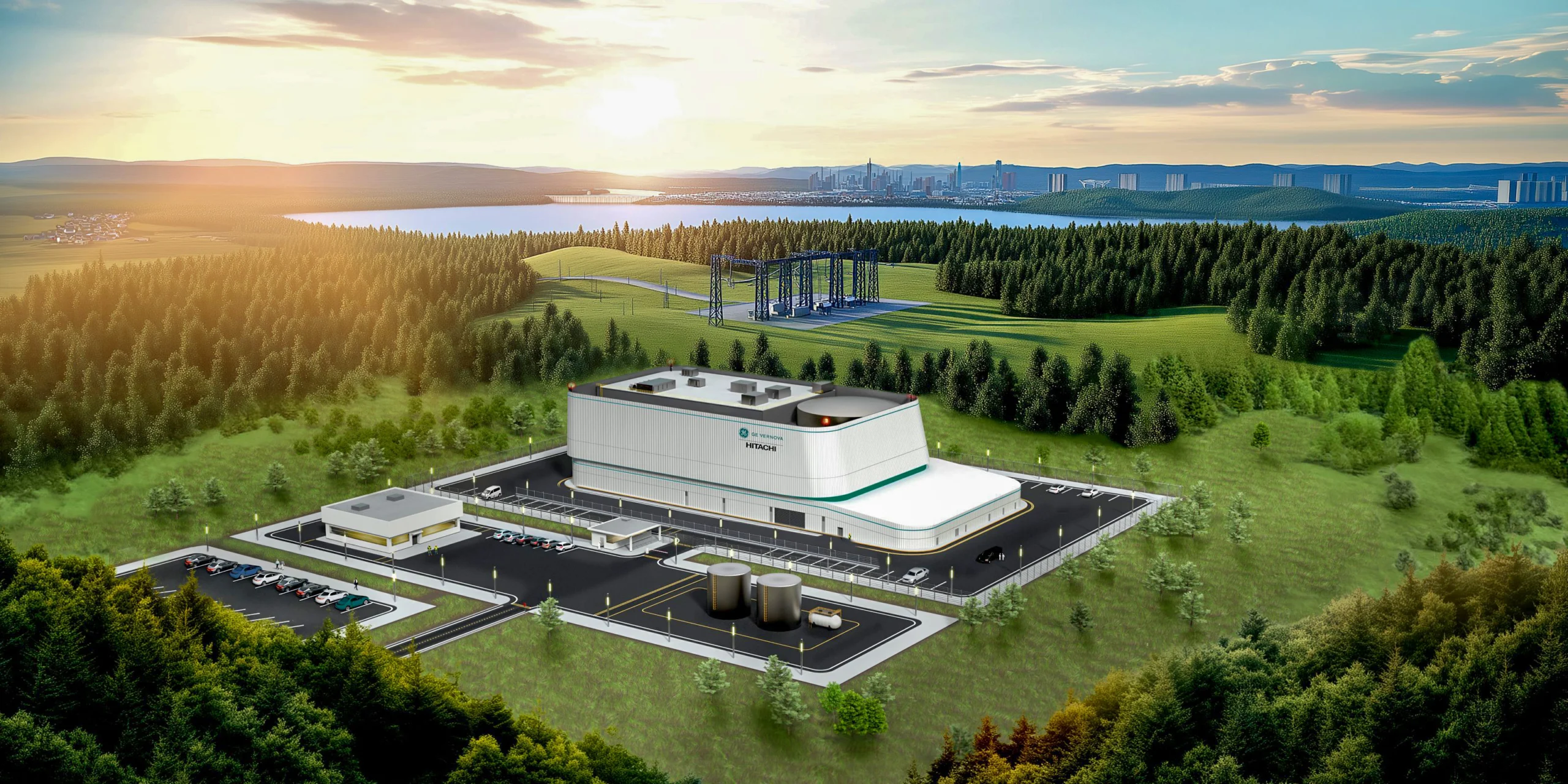

Like Vogtle, the Darlington SMR just outside Toronto is a light water reactor, a design in use around the world for decades. But like the Gen IV, it is smaller, at around 300 MW per reactor, to lower costs and reduce risk.

If all four of the proposed GE Vernova BWRX-300 reactors are built, the Canadian Building Trades Unions predicts, Darlington will create 3,700 union jobs for the next half-century. The electrical work will be done by Toronto Local 353, which has had members on site since 2023.

This project will create over 400 jobs for electrical workers building the reactor units, a switching station and transmission line integration, said Local 353 Business Manager Lee Caprio. There are at least three additional sites under consideration for development nearby.

“The first reactor is budgeted for $6 billion. The next three together should cost 25% less than the first,” said Local 353 Business Manager Lee Caprio.

The promise of the SMR is that smaller, more modular reactors will be cheaper to make, need a smaller footprint, and be less complicated to maintain.

There are working SMR plants in use, just not in North America or Europe. China brought the world’s first SMR online in 2023, just a part of the story of Chinese domination of new nuclear construction over the last 25 years.

Last year, there were 32 units under construction in China, more than half of the total worldwide. In all of North America there is only one: Darlington.

One of the most promising aspects of the Darlington development is a unique agreement between the U.S. and Canada’s federal nuclear commissions, Warren said. OPG, the project’s operator, and the IBEW partner Tennessee Valley Authority received an agreement that if one national regulator approves the BWRX design, the approval will receive “weighted consideration” from the other.

“Design approval for new nuclear technology is very, very slow, but speeding it up by lowering standards is not an option. Leveraging the work done on either side of the border makes a lot of sense,” Warren said.

If OPG receives approval from Canada, the TVA’s plans for an SMR plant in Clinch River, Tenn., will become the odds-on favorite to be the first SMR nuclear development in the U.S.

“That would be great news for us. TVA uses only union labor on their projects and the IBEW will build these units at Clinch River with our construction partners. When they become operational, the IBEW will ensure they are run safe and efficiently with our annual workforce at TVA,” said Tenth District International Vice President Brent Hall. “On a project where the craftsmanship expectations and the stakes are this high, the IBEW will deliver.”

Good Old Gigascale

Despite the hype and hope around light water SMRs and Gen IV reactors, it may turn out that the most jobs will come from the same type of 1,000-plus-MW, or gigascale, nuclear reactors the IBEW has been building for 50 years, Warren said.

Last year, Westinghouse and the White House announced a target of 10 AP1000 units, the same ones used in Vogtle. The White House also announced an $80 billion investment in the AP1000 supply chain in June. The most likely sites for those units are South Carolina, New York and Georgia, Warren said.

Construction stopped on two nuclear reactors at the V.C. Summer nuclear plant in South Carolina in 2017 when Westinghouse entered Chapter 11 bankruptcy. But in January of last year, Summer owner Santee Cooper hired Westinghouse parent company Brookfield Energy Partners to finish the project.

“They have a lot of work ensuring the structural integrity of what’s there, but company leaders told last year’s (IBEW) Nuclear Conference that it was much farther along than they had expected, around 65% to 80% complete,” Warren said.

The advantage of the AP1000, Warren said, is the maturity of the industry.

“There is a construction model, experienced partners, an existing license, a supply chain and lessons learned from Vogtle, plus all the lessons we can get from China,” he said.

Government Affairs Specialist Erica Fein said there are reasons to believe a nuclear rebirth is possible. President Joe Biden’s 2022 Inflation Reduction Act included tax credits for clean energy production and investment with strong incentives for using high-skilled labor. President Donald Trump’s budget bill last summer effectively killed those tax credits for wind and solar, but they stayed in place for nuclear.

“The president says he wants to quadruple the nuclear fleet from 100 gigawatts to 400 by 2050, and the IBEW has the men and women to do it. We were in close communication with the senior officials and the Department of Energy during the last administration. We can help answer some of these questions,” Fein said. “We just haven’t been asked. Yet.”

Future in the Balance

Light water reactors, large or small, dominated the past and are the story of the near future, but the next generation of nuclear reactors is already here.

Gen IV reactors are much more diverse than previous generations of nuclear reactors. As a rule, they tend to be small, but nearly everything else is negotiable. Coolant can be at high or low pressure. The fuel might be traditional or highly enriched. It can be in the form of rods, pebbles or pebbles encased in a carbon shell. Cooling fluids can be gas or liquid, including liquid metals like sodium and lead. Operating temperatures can be like previous generations or radically higher.

Warren said there are dozens of models that only live on a computer and a handful that have progressed to lab-based testing, but only four companies — TerraPower, Kairos, Oklo and X-Energy — have technologies that are close to commercialization.

The IBEW has agreements with at least two of them.

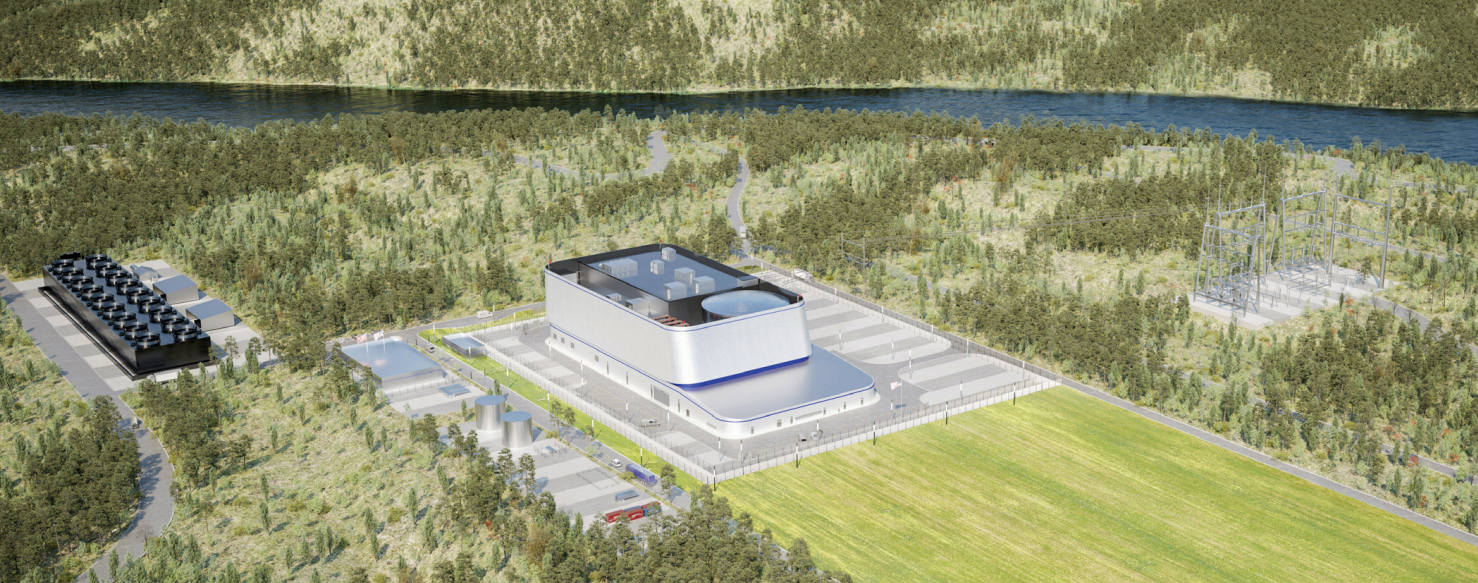

TerraPower in Kemmerer, Wyo., has a construction permit from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission but is still seeking approval for its Gen IV reactor. There is a PLA between the Building Trades and TerraPower, and two union contractors are already on site doing earth and concrete work.

Once initial foundation work wraps up in 2027, Casper, Wyo., Local 322 Business Manager Jerry Payne expects that 400 to 540 IBEW members will work there through 2030.

Payne said he hired a new organizer who grew up near Kemmerer and four months ago launched a digital organizing campaign for nonunion electricians and contractors in western Wyoming.

“It’s the perfect opportunity for a contractor to come in and see what the IBEW can offer,” Payne said.

Payne said the local is investing resources now because so much is riding on Kemmerer.

“This is a critical project because of what is possible when it is successful. It will open the door to a lot of work for a long time,” Payne said.

Warren also said the IBEW is negotiating with TerraPower to use members of Salt Lake City Local 57 to run the reactor once it is operational.

Kairos Power started construction on its Tennessee demonstration reactor last July. The site uses IBEW signatory contractors, but there is no PLA for the whole project, Hall said.

“Everything inside Oak Ridge National Laboratory is IBEW. Kairos and other Gen IV companies are building test sites just outside the fence, and I am proud to say Kairos uses IBEW because of skill set and workforce experience, but we are aggressively organizing the work outside the boundaries,” Hall said.

Warren said the IBEW has also secured a PLA for X-Energy’s facility in Washington state, though construction there is further away than either Kairos or TerraPower.

Because of their small size, greater safety, modular construction and transportability, Gen IV designs create new opportunities for the union construction and utility workforces.

“There are some districts that don’t have the workforce to handle a Vogtle. But if that district has vendors or utilities that are interested in SMRs, it is better to be able to fully man the job with the local workforce,” Warren said.

Back in the ’70s and ’80s, nuclear power jobs were a huge boon for a few years, but many locals found that they left huge headaches in their wake. Electricians who organized in to work on the nuclear projects often went back to nonunion after work dried up, trained by the IBEW and now competing with the union. Bread-and-butter industrial customers often had trouble getting their own projects manned, and in case after case, business managers found that their market share actually fell during the nuclear boom years.

Local 131’s Current hopes the smaller scale of Gen IV nuclear might offer the best of all worlds.

“I’d rather have 20 years of 100-man projects than two years of a 2,000-man project,” Current said. “They want to build hundreds of these SMRs, and I am all for it. We’ll get better at the construction; we’ll get better at running them. Support for generation based on its source changes from administration to the next, except for nuclear power. I really hope we create this wave, make it manageable and build it.”