Monroe, La., isn’t the first place you’d think of as the center of a trillion-dollar global technological revolution.

Monroe is home to 50,000 people in the northern part of the state. In all directions out of Monroe you find little but cornfields, rice fields, cotton fields and the people who farm them.

It’s been the home of Local 446 for more than 110 years, and the local has been successful in guarding its jurisdiction, considering the challenges of organizing in the Deep South.

“We have three colleges, a hospital network and the schools that have kept us busy,” said Business Manager Ken Green.

But 30 miles east, something extraordinary is happening. In Holly Ridge, an unincorporated community with one blinking traffic light, hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of earth-moving equipment is flattening 2,700 acres to prepare for the largest Meta data center in the world. At 4 million square feet — about 70 football fields — and a budget flirting with $10 billion, it is four times as large as any data center Meta has ever built.

Entergy Louisiana is planning to build three natural gas powerhouses — two on the Holly Ridge site itself — at a cost of $3.2 billion, and all 2,600 megawatts are for Meta’s insatiable servers.

Nine data centers have been announced for the campus. Four are the traditional cloud computing data centers, but five will house the cutting-edge power-gobbling chips that will train Llama, Meta’s collection of open-source artificial intelligence models.

No one knows how many electricians will be needed, Green said, but Meta has announced that it expects there to be 5,000 construction jobs.

Local 446 has 500 members, and nearly everyone who wants it already has work in the jurisdiction.

“The positive part of high market share is you have the work. The negative is that if they haven’t come in the last 10 years, they aren’t coming,” said Fifth District International Representative Brent Moreland.

Which leaves the question: How will the local find 1,000 or 2,000 electricians for five, maybe 10 years of work while maintaining what it already has?

“The explosive growth in the data center industry is a wave we are perfectly placed to ride. The stakes are high for our customers, and the work needs to be of the highest quality and on the shortest timelines. We were made for this,” said International President Kenneth W. Cooper. “We have to keep our own history in mind, though. We have to be smart about how we meet this moment. The interests of the IBEW, our contractors and customers must align if we are all going to benefit over the long term. And the long-term growth of the IBEW has to be where we focus.”

Eating the Elephant

The companies that build data centers — Meta, Alphabet, Amazon, Oracle, IBM and Microsoft — are worth trillions. They are also in a life-or-death race to build data center capacity and build it now.

Even better for electrical workers, data center projects are uniquely dependent on their skills: Between 45% and 70% of the entire budget for data center construction goes to the electrical subcontractor.

That combination of tight deadlines and no margin for error in construction means the vast majority of data center work — even in the places where IBEW market share is lowest — goes IBEW.

“About 10 years ago when our first data centers started to appear, they told us, ‘Hey, there’s going to be more.’ You’re hoping that’s true, and it ended up being true,” said Columbus, Ohio, Local 683 Business Manager Pat Hook.

“So over these years, we’ve experienced a lot of increased demand for workers. We need to grow our local and figure out some strategies to accomplish that. And we started with the owners, the general contractors and our electrical contractors on the site.”

In Northern Virginia, which has more data center capacity than the rest of the country combined, Washington, D.C., Local 26 does close to 97% of the work.

“There are only so many people in this country who are willing to do electrical work and skilled enough to do it well and safely. Whatever that number is, money is moving that same group of people around the country,” Moreland said.

Meta understands the market, and while the local’s scale is just under $30 an hour, even without a project labor agreement, the job will likely pay far above that.

Multiple locals are facing single data center projects that require two, three, sometimes four times their current membership.

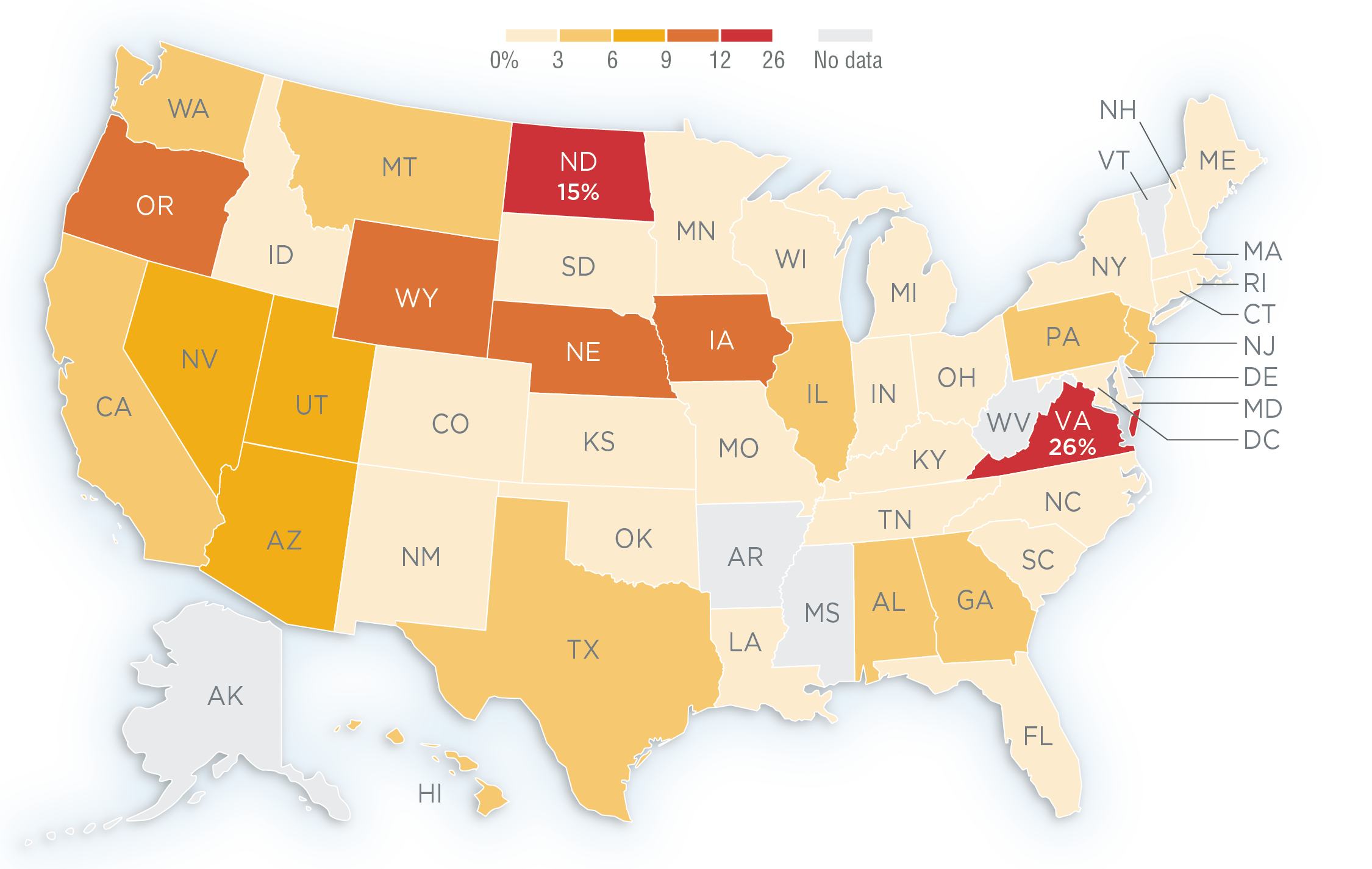

Data Centers Are Power Juggernauts

Map shows the percentage of power consumption in each state consumed by data centers.

Source: Electric Power Research Institute

For these locals, managing the growth is “like eating an elephant,” said Baton Rouge, La., Local 995 Business Manager Jason Dedon.

“At first, that elephant tastes good, but pretty soon you’re sick of it, but it’s endless. Every time you open your mouth to breathe, there’s more elephant,” he said. “And as long as you got so much elephant, what about your fields? What about your farm? Because sick as you are of eating it, even the biggest elephant ends. Then what are you going to eat?”

The data center elephant reminds Dedon of a cautionary tale about the meal Local 995 had in front of it about 40 years ago.

“Until the ’80s, we had 90% market share. This was a union town,” he said.

From where the Mississippi River entered his jurisdiction in the north to where it leaves in the south, there are dozens of chemical plants. Every one was wall-to-wall union, even after a so-called right-to-work law passed in 1976.

Then the Riverbend nuclear power plant project arrived. Hundreds of Local 995 members and travelers flocked to the job. Nearly 1,000 nonunion electricians were “white ticketed” — allowed to pay dues and work on union jobs but never made full members.

The industrial customers, let alone residential and commercial customers, were left in the lurch. Job calls stayed open, particularly calls at scale — below what Riverbend was paying.

Who needs bread and butter when you have an endless supply of elephant? Besides, Dedon said, the thinking at the time was, “We’re at 90% market share.”

But those 1,000 nonunion electrical workers, trained on IBEW jobs, became the backbone of a nonunion workforce that stripped Local 995 past the bone to the marrow. Many of the union contractors not on Riverbend walked away from Local 995 and welcomed the union-trained workforce with open arms.

“We abandoned them, so they abandoned us,” he said. “The biggest nonunion contractors were built off the guys we trained. We made the perfect storm.”

Local 995 now has 3% market share in one of the most industrialized corners of the nation.

“Just because we know what happens and have hindsight, doesn’t make solving these ‘too-good-to-be-true’ jobs any easier,” he said. “Never lose the bread and butter; those jobs will not be waiting for you when the bubble bursts.”

The Outskirts

Local 446 is not alone and will have many more locals join it in trying to learn from the past mistakes of Local 995.

Holly Ridge is just a part, albeit the largest part, of Meta’s announced $200 billion investment in data center infrastructure.

And as large as that is, it’s only the third-largest data center investment announcement this year.

In January, ChatGPT maker OpenAI unveiled an AI infrastructure plan that it claimed would exceed half a trillion dollars in just the next four years. Apple then matched that: $500 billion by 2030. Amazon committed $100 billion. Alphabet, parent company of Google, committed $75 billion.

One of the largest, a campus of data center campuses, is rising on the site of a former Alcoa aluminum plant near Frederick, Md., 60 miles west of Baltimore and northwest of Washington, D.C.

Baltimore Local 24 is anticipating a cluster of hyperscale data centers planned for 2,100 acres of forest and farmland beneath tandem 500-kv power lines. The first phase of construction includes 15 data centers and eight auxiliary buildings on less than one-third of the available land. The budget could reach $5 billion.

A total of 45 centers on this one project is realistic, said Baltimore Local 24 Business Manager Mike McHale.

“This is life-changing for Local 24,” he said.

And McHale has a plan to staff the new work while growing the local’s bread-and-butter work.

The Frederick, Md., data center project is built on the site of the Baltimore Local 24-built Eastalco aluminum plant, which was shuttered two decades ago.

As The Electrical Worker reported in March 2024, the local was essential to critical changes to Maryland law that made the development possible.

“The Frederick Chamber of Commerce is very clear — this project would not have happened without Local 24, (Washington, D.C., Local) 26, (Washington, D.C., Local) 70 and (Cumberland, Md., Local) 307,” said Local 24 Business Agent Carmen Voso.

Although there is no PLA on the project, Voso said, the developers understand the role the IBEW played, and all contracts so far have been won by signatory contractors.

The total need is not clear, Voso said, but, conservatively, they will need 1,000 IBEW members on site by August. Peak could be double that. Or triple.

Local 24 has 2,400 members.

“Our hope is that they ramp up slowly and it isn’t ‘We need 1,000 in six weeks, then another 1,000,’” Voso said.

The developers of the Quantum Frederick project built a 40-mile fiber ring called the QLoop connecting Frederick to the densest concentration of data centers and fiber connections in the world. Frederick is just across the Potomac River from the heart of the global data center industry in Northern Virgina.

“It’s a blip of a millisecond to the center of the internet,” Voso said.

Crossing the Potomac not only opens up new land, but it also breaks down a barrier that has stifled Local 24.

For decades, Local 26 and Local 24 had similar membership numbers. Then in the 1990s, data centers took off in Northern Virginia and Local 26 never looked back.

“They have about six times our membership now,” Voso said. “But we could have 2,000 on this portion of this one project. There will be more campuses and more data centers on this project. I’m not saying we will catch up. I’m just asking, ‘Why not?’”

Local 24 has lower market share than either Local 446 or Local 26, and McHale wants to use the Frederick developments not just to grow in size, but also to dominate the market.

McHale wants to use the Frederick developments not just to grow, but to grab market share at the same time.

In their favor, most of the subcontractors doing this work in Virginia are bidding the work in Maryland, and they are almost all signatory with the IBEW.

Dynaelectric DC, a division of Emcor, is one of the largest developers of data centers in the world. Paul Mella, its CEO until his retirement this year, was a 52-year member of the IBEW and director of the Washington, D.C., chapter of NECA.

Power Solutions even built a 100,000-square-foot data center prefab shop in Frederick for Virginia projects and already employs 120 Local 24 members.

Between the customer goodwill developed in the political battle and the strong, deep connections with the subcontractors doing the work, McHale has a plan to man this work.

“We want to organize every nonunion worker. Strip them all. Our examining board will meet as often as necessary to make it happen,” McHale said.

Second, the apprenticeship has nearly tripled and will continue to rapidly expand.

Finally, Voso said the trick with these projects will be to staff them while maintaining the local’s existing relationships for the hundreds of millions of dollars of projects that will happen in the rest of the jurisdiction.

“I want to crush nonunion and organize everyone directly into a job, but we can’t lose service, office, educational, hospital and stadium work in the process” Voso said.

The Baltimore rate is a substantial bump for nonunion electricians. That and an open call are the greatest organizing tool a union has.

And for the existing members who worry that money is being left on the table, Fourth District International Vice President Austin Keyser has a simple message.

“Our mission is to maximize how much you make in your career, not on a single job,” he said. “There is one and only one recipe for that: Maximize market share.”

No job, no industry, even one as rich as data centers, lasts forever, he said.

“We are the beneficiaries of the union we inherited. That includes the good — the contracts, the protections, relationships — and the not so good — lost market share from our own miscalculations,” he said. “We paid for that clarity. We better use what we learned.”