|

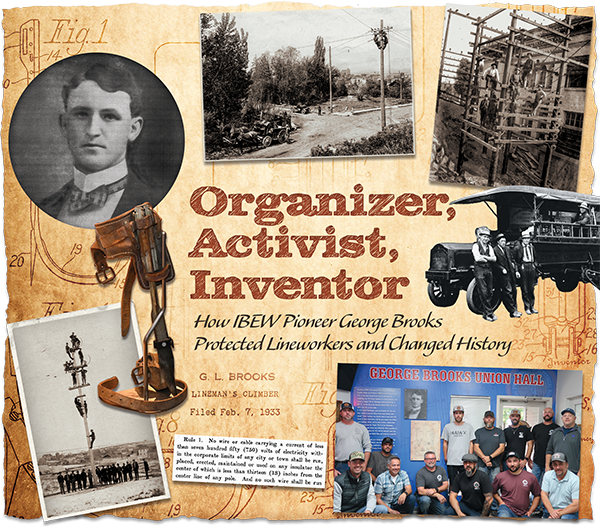

Organizer, Activist, Inventor

How IBEW Pioneer George Brooks Protected Lineworkers and

Changed History

They gathered in the lowland forests bordering Seattle, arriving by wagon or horseback for secret meetings under the shroud of towering evergreens. It was too dangerous for the young president of Local 77 and his band of brothers to discuss their plans anywhere else.

They were preparing to demand safety reforms at a time when industry-funded "goon squads" might have broken their bones, or worse, for daring to act collectively.

But taking risks was nothing new. As linemen in the early 1900s, their life expectancy was little better than a flip of the coin.

Barely one in two survived North America's deadliest job for more than three years. IBEW dues in those days had one purpose: paying grieving families' funeral expenses.

George L. Brooks, the activist leader of the local based at Seattle City Light, knew nothing would change unless labor forced the utilities' hands.

In 1913, armed with a clandestine draft of a safety code and an arsenal of arguments for legislators, Brooks and his members trekked south to Washington's capital in Olympia.

Against all odds, they beat the utility and industrial lobbies, making Washington the only state with a law protecting electrical workers, one that later would serve as a template for federal safety codes.

For the first time, the men installing poles, stringing wires, powering streetlights and maintaining the nascent electrical systems in rugged terrain and growing cities had legal safeguards, and companies could face steep fines for violating them.

Branded a troublemaker, Brooks was promptly fired from City Light and blackballed at utilities up and down the West Coast.

But the indomitable 24-year-old wasn't done leaving his mark on linemen's safety. Over the next two decades, he would invent the revolutionary Brooks Hooks that are still the model for gold-standard climbing gear.

Brooks died in March 1934, not knowing that his patent would be approved six weeks later or the impact it would have on generations of IBEW members.

Or knowing that Local 77 would grow into a powerful statewide union where his legacy is an enduring source of pride.

"His gift to our trade was bigger than what he achieved during his lifetime," Business Manager Rex Habner said. "It was a perpetuation of safety practices. Once you see one thing working, it multiplies, and that started with George Brooks."  |

Print

Print  Email

Email