January fires in Pacific Palisades and Altadena started in the hills but did not stay there. Wildfires became urban conflagrations that killed at least 29 people and destroyed thousands of homes, businesses and nearly the entire electrical distribution network in those neighborhoods.

For 24 days in January, the nightmare of an urban wildfire consumed parts of Los Angeles.

On Jan. 7, a bone-dry wind roared out of the Mojave Desert, over the San Gabriel Mountains and down into Los Angeles. The wind whipped small brush fires like a bellows in a forge.

By the time the 14 fires were under control at the end of January, 29 people were dead, 200,000 were forced to flee their homes — often with nothing more than they could carry on their backs — and at least 18,000 structures were destroyed.

They were the most destructive fires in Los Angeles history, with an estimate of more than $250 billion in total economic damage.

Whenever there is a disaster anywhere in North America, whether it’s an ice storm in the Upper Midwest or the annual parade of hurricanes in the Southeast, IBEW members are always among the first to arrive. They clean up. They repair. They rebuild. They keep the fire fighters and public safety officials safe, powered up, warm and connected.

The response to the two largest fires — the Palisades fire near the ocean and the Eaton fire 30 miles inland in the town of Altadena — required the routine skills of IBEW linemen responding to day-to-day emergency calls, but at a vastly different scale.

Workers were sent by Southern California Edison into chaos to restore order shift after 16-hour shift, some for eight weeks.

“Our linemen do scheduled maintenance, and we do emergency work on the grid: replace poles, pull wire, hang transformers, remove the old equipment. The work is the same. When it’s a tragedy, the pressure is higher and the conditions are worse,” said Diamond Bar, Calif., Local 47 Business Manager Colin Lavin.

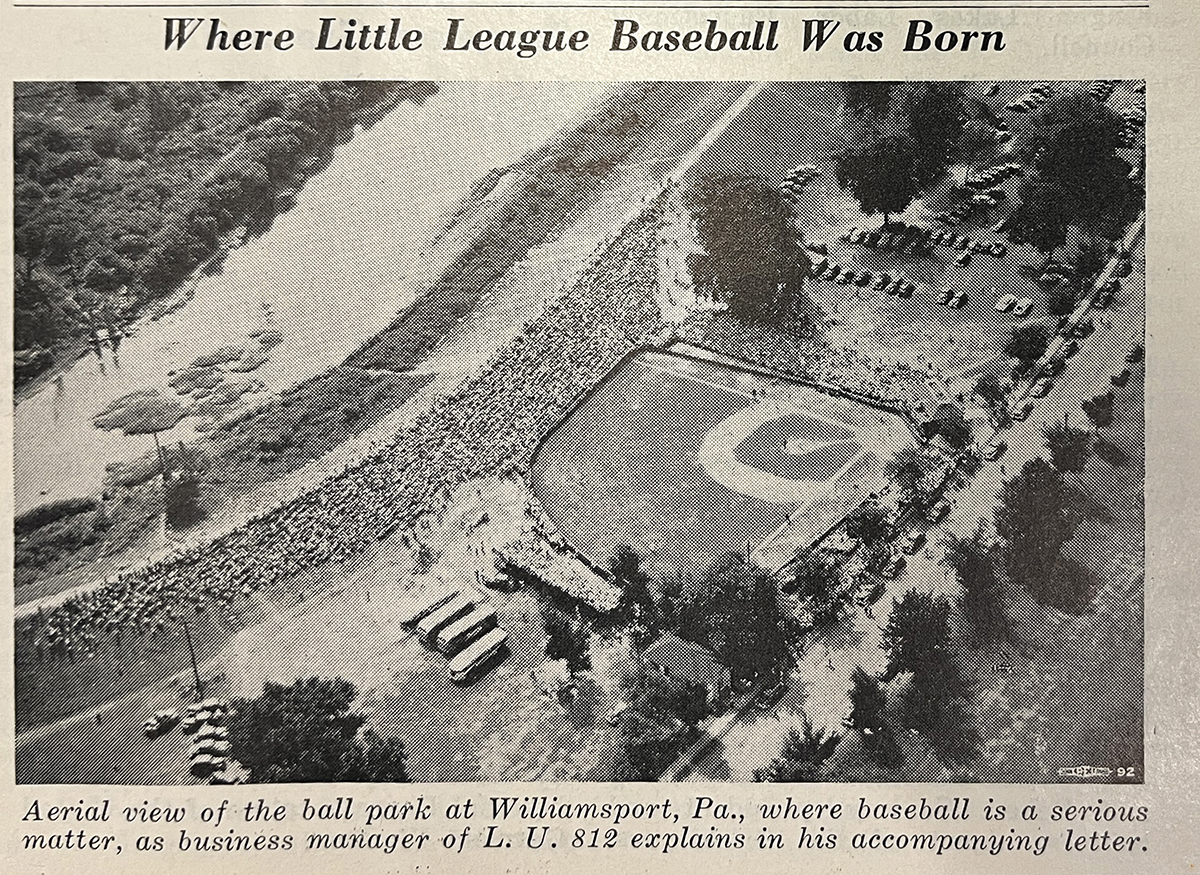

In Altadena, where the damage from the Eaton fire was concentrated, thousands of homes and businesses in the mostly middle-class community were vaporized by the fire. Lavin said close to 600 Local 47 members were assigned there in the weeks after the fire.

Local 47 Business Representative Craig Blair worked in Altadena as an apprentice and now supervises Edison crews from Orange County. Many of his crews were deployed to Altadena. As Blair checked in on them, he drove down the same roads he’d driven as an apprentice, but they were empty now, and everywhere around him was flat and gray.

“It was surreal. I have never seen blocks and blocks of city burnt to the ground,“ he said. “As far as you could see in every direction, there was just ash, a concrete pad, and then there would be one house standing. The mind has a hard time comprehending that much devastation, and then … one house.”

Blair’s crews worked from 5:30 a.m. to 9:30 p.m. Each morning, they would arrive from their hotel to a central mustering point or laydown yard at the Santa Anita racetrack. A camp kitchen hauled behind a semitruck served breakfast and provided everyone a sack lunch.

Local 47 field accounting members managed the mountain of poles, wire reels and transformers. Each night, the auger, bucket and pickup trucks came back empty, and the crews would prep the material for the following day. At sunrise, they would drive into the barren neighborhoods and work until dark.

“They wanted you done with your physical work before dark. There’s no power. It’s pitch black,” Blair said. “I know a big portion of the early focus was to get the streetlights back up.”

Crews set poles, strung conductor and hung transformers. Wherever there were surviving houses or businesses, they would install service to the house. Blair said the crews could all see one another, even though they were working in dense suburban neighborhoods.

“There were no leaves, no houses, nothing,” he said.

The work was similar at the Palisades fire, but the terrain and the neighborhoods were vastly different.

Above the famed beaches of Malibu, Pacific Palisades is a maze of canyons, said Local 47 Business Representative Jim Tice. Each canyon has a single road that weaves between a few dozen houses, some of them deep in the shadow of the mountain and others on high bluffs with views across the ocean.

In Altadena, the winds blew the wildfire down toward densely populated neighborhoods. In the Palisades, fires drove south from the heights of the Santa Monica Mountains into the valleys. In one, all the houses would be gone, but the next valley, for seemingly no reason, would be spared, Tice said.

Hundreds of people fled down the narrow canyon roads only to abandon their cars as traffic clogged and the fire snapped at their heels. A bulldozer was later brought in to clear a path through the burned and melted shells to let fire engines and repair trucks through.

The fire even jumped the Pacific Coast Highway to the mega-millionaires’ mansions lining the shore.

”I never thought I would see the sand on Malibu beach burning,” Tice said. ”There were pieces of the houses on fire, cinders blown in burning on the beach. Everything burned.”

Roughly 50 Edison crews, each made up of about five Local 47 members, met each morning at a laydown yard in Calabasas.

“One crew is replacing everything, and a whole separate group would come and collect whatever was left of the old,” Tice said. “The fire doesn’t disintegrate wires, but they melt. Cars melt. There might be a stub of a pole. Most of the wire is on the ground, but it is in pieces.”

It wasn’t only linemen called into emergency service.

Los Angeles Local 45 President Rita Martinez is a data communications technician and steward for the City of Los Angeles Information Technology Agency. When the fire tore through the northern edge of the city, it destroyed critical equipment in the first responders’ communications network, cutting off three fire stations at the heart of the struggle.

“The networks for the fire department all went down. All their fiber lines and hubs were burned,” she said. “Where we were working, the smoke was really dense. The houses, businesses, they were flattened.”

Martinez and crews from phone, microwave and data groups converted the entire communications network from wired to wireless and reconnected the firehouses to the city command post.

“We had to run generators to power everything and reconfigure the equipment to let it talk to the network. And we had to run cables up to new receivers or access points to carry the signal down into the station,” Martinez said.

Crews split into 12-hour shifts and worked around the clock until the job was finished.

Lavin, Los Angeles Local 11 Business Manager Robert Corona, Local 45 Business Manager Rodney Cummings and Local 40 Business Manager Stephan Davis created a hardship fund for members affected by the fire. Eventually, it will accept donations from any IBEW member or local, Lavin said.

But the area’s locals and IBEW members haven’t waited. Tens of thousands of dollars have already been donated to brothers and sisters who lost all or part of their homes or had to evacuate for days at a time.

Local 47 members working in Paradise donated about $30,000 to the community, a number that some signatory contractors matched, Lavin said.

The Local 11 Veterans Committee cleaned up the wreckage from a member’s burned out garage, Corona said, but that’s only one of the acts of kindness he knows of. He said he expects to hear about many more in the coming weeks.

”You don’t know what you can do, but you want to do something, so we put together care packages to deliver to shelters — feminine products, toothpaste, toothbrushes, body wipes. You don’t grab that when you could grab a picture or things you got from your parents,” Corona said.

They also put together supplies for the nearby fire station: coffee, water, snacks. They needed a police escort to deliver it, Corona said.

How the Los Angeles locals choose to support the wider community hurt by the fires is a decision they are leaving until the severity of the situation is more clear.

“Our local hall is in Pasadena, not far from Altadena. On that first day, I received calls from so many people who said to me: ‘I have to leave my home. I am gathering my stuff right now,’” Corona said. “It’s terrible, but it could have been so much worse. We lost too many people, but, thank God, most of what people lost is property. And we know how to build.”