Brian McPeek II’s father worked nonunion almost his entire career. Until last year.

“He wasn’t doing construction. He worked a lot of maintenance jobs. Then the solar job comes along. The stars align. He is now IBEW for the first time in his life and making journeyman wages and benefits,” said McPeek, business manager of Mansfield, Ohio, Local 688.

Five years ago, this wouldn’t have been possible. Grid-scale solar was being built, but the IBEW had less than 10% of the market in the state.

Today, that number is about 90%.

The meteoric rise is the result of an unlikely coalition, one that started as strangers in a foxhole and has now developed into a formalized partnership among the IBEW; the Operating Engineers; the Laborers; solar developers; and, crucially, one of the largest environmental advocacy groups in the world, the Natural Resources Defense Council.

They’ve all come together because the multibillion-dollar utility-scale solar construction industry in Ohio is under attack.

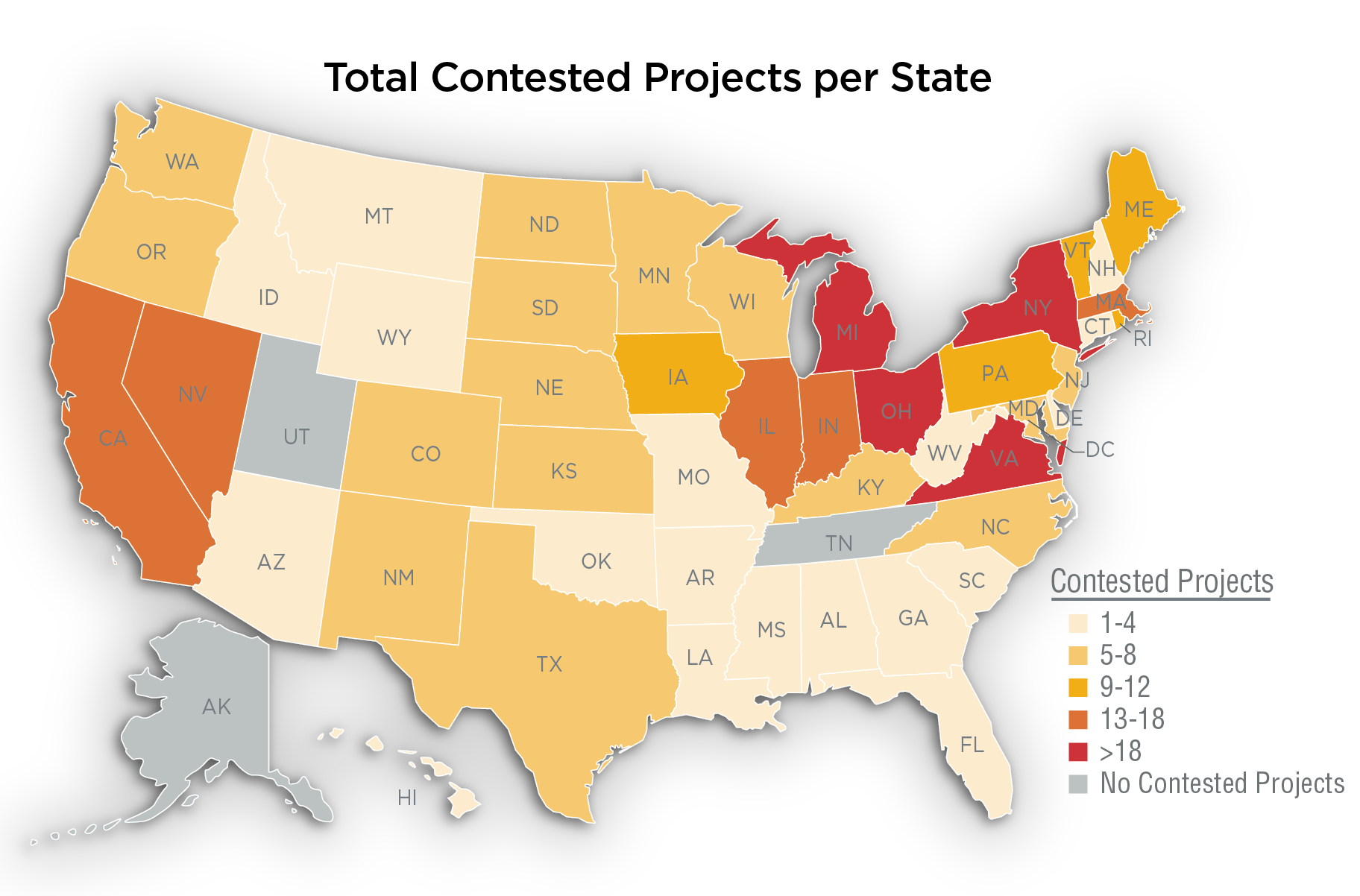

A wealthy and deceptive dark money campaign has been killing hundreds of solar projects, threatening the hard-fought progress of the past few years not just in Ohio but across the country. Indiana, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Virginia and even California have had dozens of projects stalled, hindered or outright blocked in the last few years.

In county after county, money from who-knows-where flows in and props up a local-sounding group. They whip concerns into a fear that becomes anger. Residents influenced by the campaigns testify in public meetings against solar and wind farms. Projects that promised jobs and public funds for schools and roads wither and die.

“In Richland County [Ohio], where I live, there are no proposals for solar projects, but 11 out of the 18 townships banned solar projects,” McPeek said. “Until a few years ago, these solar projects were godsends. No one else is coming here with a $350 million project.”

Median household income in Richland County is $57,000, according to the U.S. Census — compared with more than $80,000 nationally — and almost one in five children live under the poverty line. The Richland County seat, Mansfield, home to International President Kenneth W. Cooper, was an industrial town a few generations back, so it has been shocking to McPeek how aggressively some residents have trashed projects that would provide hundreds of high-wage, career-building rural jobs.

“It’s crazy,” he said.

Dark Money, Loud Message

Grid-scale solar projects are almost uniquely good for union workers. Ohio law gives solar projects a special tax status if they have at least 70% in-state workers.

Another huge boost for union workers had been the Inflation Reduction Act, which provides federal tax benefits when developers follow Davis-Bacon prevailing wage laws and use registered apprentices. But the worker protections in the IRA have been gravely weakened by the passage of President Donald Trump’s budget bill (See editorial, The Great Betrayal, for more details.)

“On average, for every megawatt of solar in a project, there are two full-time union jobs for at least two years. A 350-megawatt project is 700 jobs,” said Fourth District International Representative Aaron Brown, whose duties cover renewable energy and government affairs in the district. “Even better, these aren’t jobs where our members who live out in the country have to drive hours into the city or leave home for weeks and months at a time. This is years of work where you are home for dinner every night.”

Grid-scale has also been a valuable organizing tool. Local 688 has close to 300 members and is at full employment. Stripping nonunion workers is much simpler when there are available jobs that don’t require a journeyman certification but pay journeyman wages. It’s an enormous, and rare, opportunity for the people looking for work in these rural communities.

“We’re stripping nonunion apprentices and sending them right to work because there are no CE/CWs on these jobs,” McPeek said. “We pulled in three recently who just finished their nonunion apprenticeship, classified them internally as CE/CWs until we could get them tested and sorted, and still sent them out on journeyman wages. They have since tested in as journeymen and are working on other projects.”

But over the last half-decade, McPeek started to see something he didn’t understand at first. Opposition to wind and solar projects rocketed up out seemingly nowhere. And somehow, opponents always had the money to get the word out. Mailers. Pamphlets. Spam text alerts. Yard signs. In Knox County, a Pro Publica investigation found that solar opponents even bought the county’s only newspaper, the Mount Vernon News.

All the messages were the same, too:

Solar was “woke energy.”

It was especially bad for farmland.

It was ugly, even if you couldn’t see it from any road.

And lack of beauty was all of a sudden a good enough reason to tell people what they could and couldn’t build on their own land.

Turbines caused tornadoes.

The solar panels were part of a Chinese government conspiracy to take control of the North American power grid.

“We’re not even installing solar panels from China!” McPeek said, adding that there are panel factories near Columbus and Toledo.

In return for an agreement to use union labor, PYC will train IBEW members to advocate for clean energy projects in Ohio and soon Pennsylvania and Virginia.

Plotting to Kill an Industry

These arguments were not coming from a handful of powerless busybodies.

“Projects were dying,” Brown said.

The tipping point came in 2021, when the Ohio governor signed S.B. 52, empowering counties to stop solar and wind development. Counties couldn’t stop chemical plants, feed lots, strip mines or fireworks factories, just grid-scale solar over 50 MW and wind over 5 MW.

“It’s all so weird and un-American,” Brown said.

Concerted, well-funded and eerily similar campaigns popped up like dandelions.

“They all started as local campaigns but always founded by someone wealthy. And they always had a huge amount of money to spend,” he said.

The funding was too big to be local and the message too consistent to really be about local concerns. Because it wasn’t.

For example, in Knox County, opposition to the Fraser solar project went by the name Knox Smart Development. In September of 2024, founder Jared Yost testified before the Ohio Power Siting Board, which must approve all grid-scale solar projects. Yost denied that his organization had taken any money from “individuals or entities having any interest or providing any goods or services to the fossil fuel industry.”

But under oath, Yost admitted that two of his largest funders were Tom Rastin and his wife, Karen Buchwald Wright, who own one of the nation’s largest methane compressor companies.

“Rastin sees the economics of his industry failing. He’s not interested in changing his products — he is stuck in the 1950s. He wants to get us stuck in the loop with him,” said Dan Mogerman, spokesman for the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Anti-clean-energy groups have been remarkably successful. More than a quarter of Ohio counties — nearly all of them rural counties with space and proposals for large-scale solar — have instituted near-total bans.

“This law only allows you to stop solar and wind. You don’t want a munitions factory next door? Too bad. You want to build a feed lot? Go right ahead. You want to tear up your fields and build apartments as far as the eye can see? Be our guest. But if you want to keep your farm and lease the land to a solar company, well there the government puts in its boot,” Brown said.

It was all upside down.

The alliance between the IBEW and the Natural Resources Defense Council, known as Power Your Community, fights for landowners’ rights, for union jobs, and for a clean energy future.

Building an Alliance

And just as unusual was who kept showing up to fight for the union-built projects. From the statehouse to the Power Siting Board to county zoning commission meetings to township meetings, standing on the same side as the IBEW was an unexpected ally: Dan Sawmiller, the Ohio director of energy policy for the NRDC, a global environmental advocacy and policy organization.

“It started organically. When we first started talking, there was small-scale opposition to specific projects, but they weren’t major hurdles yet. All of a sudden, we had tiki torches and pitchforks at every meeting,” Sawmiller said.

After S.B. 52 passed, Fourth District International Representative Steve Crum and Sawmiller started talking. They quickly brought in Jon Rosenberger, director of business development, who brought in Gina Cooper, then the Fourth District international vice president.

“As we built the relationship, we realized this is unique. Dan can get into rooms we can’t, and we can get into rooms where they can’t,” Rosenberger said. “We complement each other.”

Solar development is a complicated, fast-evolving industry. Few developers have deep connections to unions or to the communities where they planned to build. They had project plans, money and leased land, but the opposition was strangling their projects.

The IBEW could get members who live in every county to argue for development, but Rosenberger said it was nearly impossible to find the people in the industry who could or would make a commitment to use union labor.

The NRDC, on the other hand, knew exactly who in the industry was making the decisions, and it brought policy chops and campaign expertise that helped determine where and when to intervene. But it is a global operation, and town-by-town organizing is not where it excels.

“I learned that I have a partner I can trust to get the job done. If I put my neck on the line for the union, they will deliver. … We need a commitment to use union labor or we will not engage.”

Dan Sawmiller, the Ohio director of energy policy for the NRDC

Developers were nervous about unions. The IBEW was uninterested in putting time or members’ dues and effort to get a project approved without written agreements.

The bridge was built on Zoom calls and in informal meetings.

“It’s a virtuous cycle. We are not just getting more of the work, but we are making sure there is more work overall,” Rosenberger said. “Before, we reached out to developers, and they would call us back when they got around to it if at all. Now they call us with an agreement already signed.”

It hasn’t been seamless. In the early days of the partnership, when things were more informal, a solar developer went with nonunion workers on the Hillcrest project after the IBEW had intervened, Sawmiller said.

The developer wouldn’t budge, but when the contractor ran into trouble, Sawmiller made it clear to the developer how he saw it: They had to get the IBEW on site.

The developer did hire a union contractor, and the members did what they do. The problems were fixed. The project was back on schedule. Budget targets were met.

“I learned that I have a partner I can trust to get the job done. If I put my neck on the line for the union, they will deliver. I can take this risk,” Sawmiller said. “Now it is ironclad. We need a commitment to use union labor or we will not engage.”

The partnership was formalized in 2024, when Cooper and NRDC President and CEO Manish Bapna signed a memorandum of understanding creating Power Your Community, or PYC, a collaboration to get more clean energy generation built in Ohio and have all of it built union.

“We were already doing the work. We just put a name to it,” Mogerman said.

And the results for IBEW members are there to see. With market share approaching 100%, solar developers are starting to compete in the wider pool of union electrical workers. For the first time, Columbus Local 683 negotiated a per diem on a solar job, $100 a day.

“It provides work for our rural members who always had to drive into the city, and because of the size of the projects, we can recruit people who would normally only be a CE or a CW and start their career,” said Business Manager Pat Hook. “I think between 75 and 100 of our apprentices started out on a solar project.”

PYC clarified roles and goals and allowed the group greater access to philanthropic support. The PYC will fund and run trainings for members to speak more effectively at public meetings and hearings. It will become a statewide hub to coordinate the strengths of each of the partners as they fight for union jobs

It also sets a template for expansion, to Virginia in the Fourth District and Pennsylvania in the Third District.

“We used to fight on opposite sides of projects,” Rosenberger said. “With renewables, we are learning just the same as them. But the more common ground we found, the more common ground we found we could make. There is more to this relationship.”