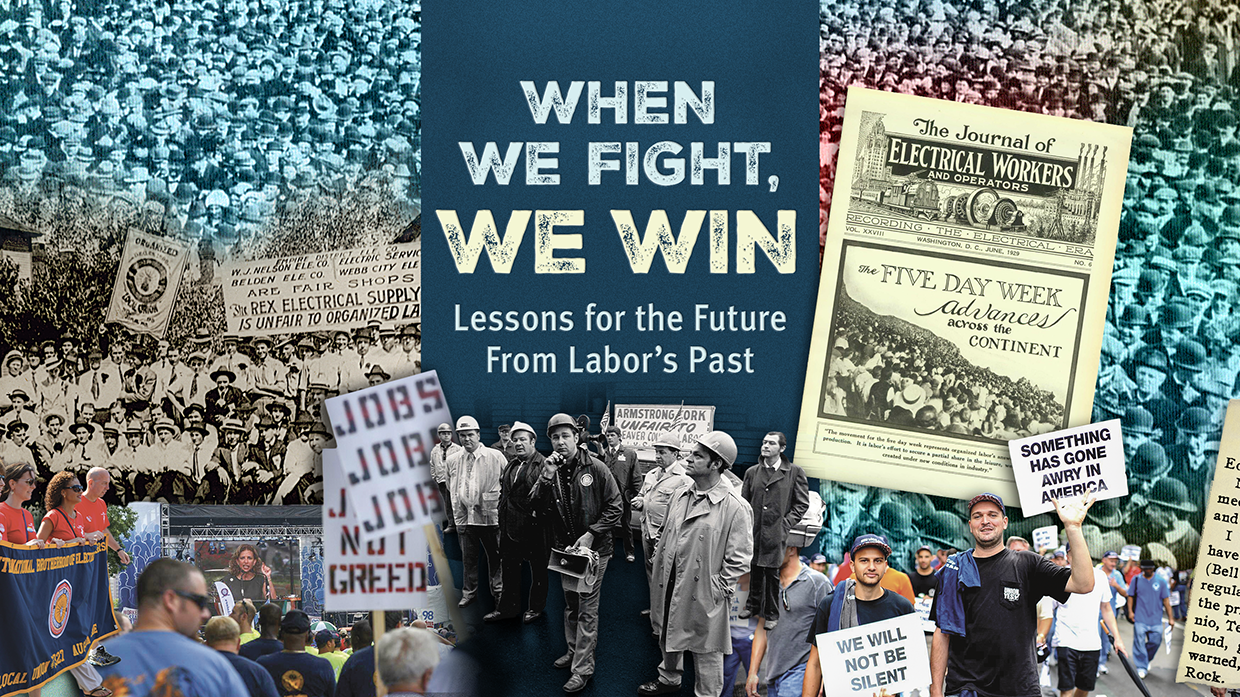

THE APPRENTICES in Erin Sullivan’s “Principles of Trade Unionism” class start out like most young workers in the 21st century. Or like most workers of any age today: They know little about the history of unions and why it matters.

Who fills out a timecard and wonders why there’s an eight-hour day instead of 10 or 12 or 14? Why the work week is 40 hours instead of 50 or 60 with no overtime pay? Why they’re not breathing toxic fumes on the job or trapped behind locked doors?

Men and women generations ago fought for fair hours, fair wages and early safety rules in the most literal sense, putting themselves in danger to make their voices heard.

Rallies, marches and strikes that began peacefully turned violent when union-busting thugs, baton-wielding police and armed militias showed up. Protesters were thrown in jail, beaten and maimed, shot and killed.

“Erin’s class really opened my eyes,” said first-year apprentice John Tomsen of New York Local 3, which mandates that apprentices take the introductory course while earning an associate degree.

“Everything that we take for granted had to be earned,” Tomsen said. “People risked their lives for what we have today. They died for this movement.”

The brutality carried out with impunity against workers in the 1800s and early 1900s is in the past. But the fight isn’t, as Sullivan, a Local 3 journeywoman, emphasizes to her students.

“We may have a 40-hour week and we may not have children working in mills, but we really haven’t progressed since the National Labor Relations Act was passed in 1935,” she said. “There are some places we never got and some places where we achieved things that we’re now seeing be rolled back.”

The outcry against the NLRA began immediately. Business leaders turned to the courts and Congress and in 1947 won passage of the infamous Taft-Hartley Act, ushering in state “right-to-work” laws and other restrictions on labor. Since then, aside from the rare pro-union hiccup, legislative and judicial assaults have battered workers’ rights.

“There’s a reason that unionization in the United States fell from one-third of all workers to just 10%, and it’s not because they don’t want unions,” International President Kenneth W. Cooper said. “The polls consistently show that most workers would join a union if given the chance. But powerful people bankrolled by billionaires and corporations are once again taking that choice away from them.”

A dramatic shift between 2021 and 2024 brought White House policy repairs, worker-friendly appointments to labor boards and other progress toward revitalizing unions and rebuilding the middle class. Petitions for union elections skyrocketed at the National Labor Relations Board, as did unfair labor practice claims against law-breaking employers, a sign that workers believed they’d get a fair shake.

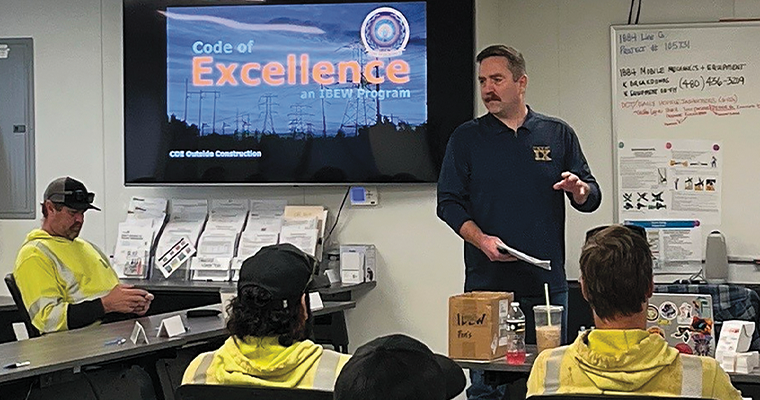

Today, favorable policies are being rescinded, rule-making boards have been stacked against unions, and staff has been slashed at agencies responsible for workers’ rights and safety. Among other rollbacks, some 60 Occupational Health and Safety Administration rules — adequate lighting at construction sites, for instance — are on the verge of elimination. (See “Code of Excellence Helps IBEW Members in Oregon Quickly Smooth Project’s Start.”)

Labor’s past, as the movement’s leaders and historians know all too well, is never fully in the rearview mirror.

“It’s why I tell my students it’s important for them to show up and fight,” Sullivan said. “I tell them, ‘This is your struggle now.’”

EARLY IBEW members were most likely to encounter violence and face arrests when marching and picketing in solidarity with other unions.

On their own, electricians fighting for change weren’t met with the same level of force as other worker groups. But they weren’t immune from harm.

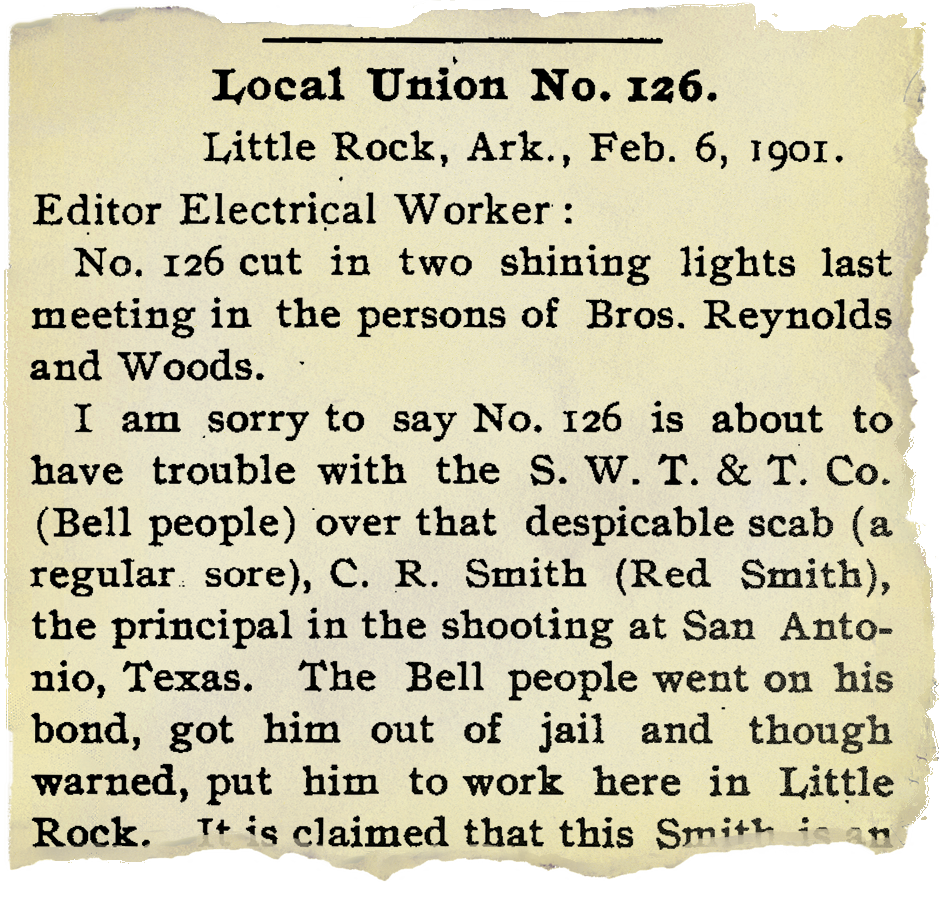

“We are sorry to announce to the readers of the Electrical Worker that there has been blood spilled over the strike in San Antonio, Texas.”

That was the opening line of a December 1900 report from the press secretary of Local 60 at the San Antonio Telephone & Telegraph Co., during a time of worker uprisings at Bell companies nationally.

San Antonio linemen were striking for $3 a day and eight-hour shifts. Contractors backed them, as did a businessmen’s club that “took the matter up, investigated and decided our demands reasonable and concluded to do without their phones until the strike is settled.”

The Bell System dug in, pledging to spend $100,000 to crush the strike and replacing workers with scabs. “These rats know they sacrifice every bit of manhood when they take another man’s job during a strike” was on the tepid side of the union’s rejoinders.

On Thanksgiving Day 1900, a scab and known local menace named C.R. Smith pulled a gun and wounded at least two strikers, hitting one near the spine. Smith reportedly taunted the workers — asking how they liked being out of a job — then fired his revolver when they gave chase.

An April 1901 update on the man shot in the back read: “Bro. Blanton has moved to Austin. We all hope he is getting along well. Just think of it, brothers, the life of a good man blasted forever by a paid assassin of the Southwestern.”

Shockingly, the Bell System posted Smith’s bond. “They got him out of jail and put him to work here in Little Rock,” Local 126, then based in Arkansas, wrote in February 1901.

That would be unimaginable today, Cooper said.

“No employer would bail out an attacker, give him a new job and risk being liable for more workers being hurt or killed,” he said. “As tough as things can get when we’re fighting for a fair contract, we’re able to exercise our rights in relative safety. Our brothers and sisters a century ago had no such guarantees.”

After dragging on for months, the strike was only minimally successful, like many job actions before union rights were affirmed by the NLRA and enforced by the NLRB.

But it was decades of workers’ persistence and courage that made those reforms possible, the cumulative impact of solidarity on a massive scale.

NEW YORK CITY is one of the cradles of America’s labor movement, the site of early and epic worker protests, the home of famous agitators, and the birthplace of Labor Day.

But uprisings took place coast to coast, from the famous “Bread and Roses” textile strike in Lawrence, Mass., in 1912, to the mostly peaceful Seattle General Strike of 1919. IBEW members were among the participants in what is believed to be the nation’s first general strike.

In Haledon, N.J., just outside New York City, Pietro and Mario Botto opened their home to workers leading the Paterson Silk Strike of 1913. On Sundays, fiery labor leaders on the balcony rallied as many as 20,000 strikers and allies who fanned out for blocks.

The Botto House, furnished to show how the family lived, opened as the American Labor Museum in 1982. It was designated a national landmark a year later, one that gets special care from the IBEW in New Jersey, particularly East Windsor Local 827, Paterson Local 102 and Cranbury Local 94.

“The only uniting factor was the cause of working people.”

– Tom Kelly, Local 827 business agent, on worker solidarity during the 1913 silk strike.

“We are totally indebted to the IBEW,” said Angelica Santomauro, the museum’s director since 1992. “They have been a major contributor from the onset, both financially and with labor.”

With educational and cultural events dedicated to telling the story of the labor movement through all unions past and present, the museum is the only one of its kind in the United States.

“We’ve been called ‘labor’s schoolhouse,’” Santomauro said. “It’s really all about education. We’re not a dead museum where you walk through, look at artifacts and leave.”

Formerly a New Jersey schoolteacher, Santomauro created a curriculum for her middle schoolers around labor history and solidarity. Under her watch, they formed the “6th, 7th and 8th-Grade Student Union” and negotiated a contract with teachers and administrators, drawing coverage from The New York Times and TV stations.

Tom Kelly, a Local 827 business agent and president of the Passaic County Central Labor Council, is among IBEW leaders and members who marvel at Santomauro’s devotion and creativity.

“The labor movement could not have a better steward of our history,” Kelly said. “Angelica’s been doing this a long time, and she hasn’t lost any of her vigor.”

Kelly holds steward trainings at the museum, brings apprentices on tour and is at the ready to help with repairs. As many times as he’s heard Santomauro and education director Evelyn Hershey give tours, it never gets old.

“They don’t give room-to-room tours, they give wall-to-wall tours — heck, nail-to-nail tours,” he said. “They are so knowledgeable and passionate about it. It moves me every time.”

He has a special fondness for the grainy black-and-white photos of thousands of ordinary people standing in solidarity during the silk strike.

“They weren’t united by race or religion or even language,” Kelly said. “The only uniting factor was the cause of working people.”

FOR MANY visitors, the 130-year-old Botto House is their first exposure to labor history. For some IBEW members, it’s a bonus of volunteering their electrical and handyman skills.

Micheal Dasaro, a newly minted journeyman at Local 102, said working among the exhibits made an impression.

“I didn’t know about labor history and all the other unions that were involved, the Teamsters, the Operating Engineers, food industry workers, stagehands,” he said. “You see them at the Botto House and you realize that all of our unions played a part to make America what it is.”

Dasaro was recruited to help by Mark Battagliese, a Local 102 business representative who is being honored this fall as the Botto House’s volunteer of the year for his lighting and maintenance work.

Battagliese vaguely recalls a trip to the museum as an apprentice. But he said he’s absorbed more while helping out over the past year, connecting dots he hadn’t before.

“I didn’t grow up knowing about the silk factories here,” he said. “They were just run-down buildings. We’d drive past and my mother or grandparents might say, ‘That’s where your great aunt worked sewing suits.’ The Botto House reminded me of that. I think that’s what it does, gets you closer to the past and gives you a better understanding.”

Dasaro also realized he was awash in his own community’s labor history. “It’s really eye-opening to see how much happened near me. It’s so close to home. I had no idea.”

He encourages his IBEW brothers and sisters to learn more, too.

“We’re in a time where we have a very good living wage, very good benefit packages,” Dasaro said. “We need to learn what it took to get here, because it took a lot and there’s still more we can do.”

Classmates and feature subjects Wil DeJesus, left, and John Tompsen at their first job site.

WIL DEJESUS didn’t know what to expect when he enrolled in Erin Sullivan’s class in spring 2025.

“The first day of class, she had one person pick up a table. Then she had three or four more people go help, and the table went up a little bit easier,” he said.

“Eventually, the whole class was helping. You realized that everyone just needed one hand, that no one was killing themselves. It really showed the message of being in a union, being there for your brothers and sisters.”

DeJesus graduated from college expecting to work in the medical field, but a lab job left him wanting more. Then his mother, a Javits Center employee, heard about Local 3 apprenticeships from some of the convention center’s electricians.

Like his classmate John Tomsen, DeJesus was unaware of the ways that long-ago worker solidarity affected his daily life.

“Like it’s always been an eight-hour day,” he said. “I just thought it was more of a norm, a cultural thing. I never thought about how it was established.”

To the surprise of both young men, Sullivan wasn’t just their instructor at the Harry Van Arsdale School of Labor Studies, a unit of Empire State College named for Local 3’s business manager from 1933 to 1968. She also turned out to be the foreman at their ongoing first job, refurbishing a hospital in the Bronx.

“It’s a unique experience to have a teacher who works in the field,” DeJesus said. “It made me very receptive to everything. I knew I had to listen and take it all in.”

As did Tomsen. “I feel really lucky to have my teacher also be someone who’s on the job with me every day,” he said, noting that excuses for late homework are out. “You can’t really complain that you’re tired or too busy.”

Sullivan, who’s taught the class since 2013, has a 10-page syllabus that includes projects and papers. But her primary mission is demonstrating the power of connection and unity. Sharing and listening are key.

Her students reflect Local 3’s long commitment to diversity, from gender, race and ethnicity to the disparity of being raised in the projects or relative wealth.

“There’s something real to each side,” she said. “You’ll have a woman who grew up in generational poverty and we have to acknowledge that. But you’ll also have a kid who grew up in the suburbs and went to private school. We can’t marginalize him because he had privilege.”

Sullivan, who’s taught the course since 2013, recalled worrying about one student’s attitude when a Middle Eastern classmate told his family’s story of immigrating to America.

“He says, ‘Things were going really great and then 9/11 happened. People would get up on the train and walk away from me and say terrible things,’” she said. “And this kid, who I thought I was going to freak out, went up to him and gave him a bro hug and said, ‘Thanks for sharing that.’”

Among field trips, her spring semester students attend the annual memorial mass at St. Patrick’s Cathedral for fallen construction workers.

“We had to wear our hard hats,” DeJesus said. “And I remember this one moment when the priest was talking and I just got goosebumps. Like a random moment, that feeling that we’re all here for one purpose. That’s it’s bigger than just us, all the trades being here together for each other.”

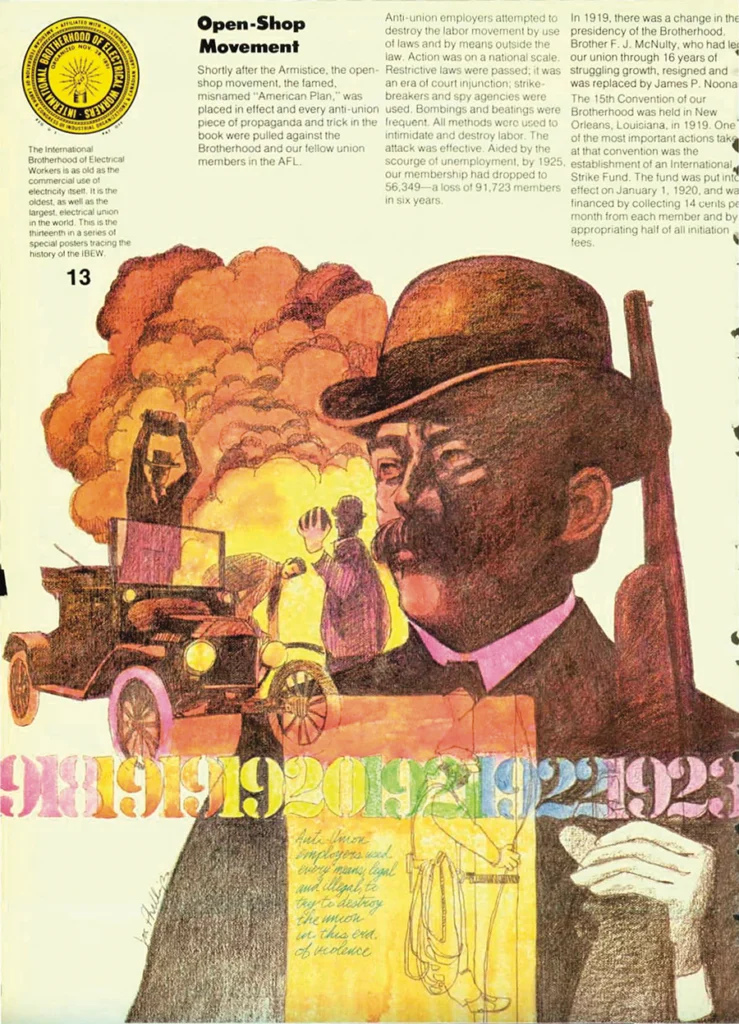

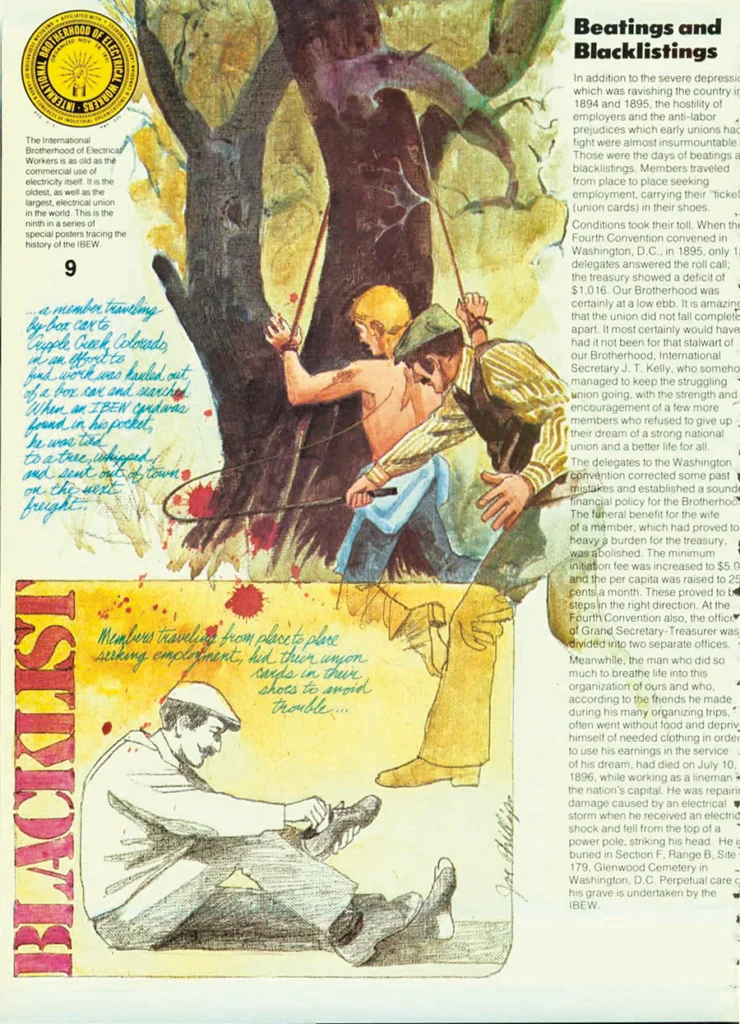

Labor history posters from mid-1970s editions of The Electrical Worker.

EVERY STUDENT of Sullivan’s does a presentation on a U.S. labor leader. DeJesus’ was the most contemporary, profiling AFL-CIO President Liz Shuler, an IBEW sister out of Portland, Ore., Local 125.

Tomsen was surprised to be assigned Martin Luther King Jr. “I thought he was mostly a civil rights leader,” he said. “I had no idea how much he did for the labor movement.”

Through his research, he learned that King believed the movements went hand in hand and that good, union jobs were the path out of poverty for minorities and all Americans.

“One quote from him really stuck with me,” Tomsen said. “What good is having the right to sit at a lunch counter if you can’t afford to buy a hamburger?”

It shook him to learn that King was in Memphis, Tenn., to support striking sanitation workers when he was killed on April 4, 1968. “They were severely underpaid and working in unsafe conditions, and he was fighting that. And he was murdered.”

Tomsen saw that today’s safeguards on the job are directly connected to courage like King’s and the countless tragedies that took workers’ lives. “If there’s something off at a worksite, we can talk to a shop steward or call the DOB (Department of Buildings) to report it,” he said. “That didn’t used to be the case.”

But his presentation and others’ made him realize how much is still on the table. “All these things that labor leaders were fighting for, so many of them are still a struggle — like right-to-work,” Tomsen said, referring to the anti-union laws that allow workers to benefit from representation without paying their fair share.

“That was an issue in 1968, and it’s still an issue today in so many states around the country,” he said. “The fight never really ends.”

LEST ANYONE doubt there’s a live wire between labor’s past and present, Local 827’s Kelly has a story to tell about the legacy of one of the two workers killed during the Paterson silk strike.

While the IBEW and Verizon enjoy a good relationship today, tensions were high in 2016 when 40,000 IBEW and Communications Workers of America members struck the telecom giant.

One day, a member alerted Kelly and one of his chief stewards, Andy Newman, that he’d seen a Verizon sales tent being set up outside a card shop a few miles from Paterson. They knew such promotional tie-ins can benefit small businesses, but they had to respond.

“We called on everyone to converge on the shop and shut the event down,” Kelly said. “After a few calls, we had 100 union members with picket signs on their way.”

Meanwhile, a friend of theirs with a business near the shop offered to call its owner and explain the situation.

“He called us back a few minutes later, baffled by what just happened,” Kelly said. “When he told his friend Frank, the owner, about the Verizon strike, Frank started yelling at the Verizon salespeople and told them to get off his property.”

Kelly and Newman were stunned. “The next day we called the owner. We told him we knew it was a big deal for his shop to have the Verizon event and we were curious why he did what he did.

“First he apologized, saying he had no idea we were on strike. Then he told us that his great-grandfather Valentino Modestino was shot and killed on the picket line during the silk strike of 1913. He died while holding his — Frank’s — grandmother in his arms.

“Frank told us, ‘As soon as I heard “strike,” I threw them out. It was a done deal.’”

On Kelly’s next visit to the Botto House, Santomauro confirmed the story with yellowed newspaper clips.

“It was one of those moments where everything came full circle,” he said.

Priests at NYC’s St. Patrick’s Cathedral honor fallen workers at a May memorial mass (Photo courtesy of New York City Central Labor Council) attended by Local 3 apprentices learning labor history in a class taught by journeywoman Erin Sullivan (front center).