The origin of the name, however, dates back much further. In 1931, it was IBEW members who first converted their helmets to hardhats and introduced a fundamental piece of safety equipment now used around the world.

In October 1931, a 25-story post office building was under construction in Boston. As the Ironworkers traversed wooden planks on the upper floors, members of IBEW Local 103 began electrical work on the lower floors. In those days, it was customary for the stray bolt, nut or rivet to fall through the planks, but on this particular job the incoming barrage had become an epidemic.

In an article from the December 1931 Electrical Worker, Local 103 members detailed the dangerous working conditions. “Red-hot rivets have been plunging down through the web,” Local 103 Business Manager George Capelle said in the article. “John Shannon received a fracture of the skull Tuesday while working on the third floor. Gus Chipman was treated for a head injury yesterday. And this morning Augustus Chapman was injured. All are now at Haymarket Relief Hospital.”

The electrical workers weren’t the only ones in harm’s way. Injuries were reported by the Teamsters and the Carpenters. The Ironworkers themselves “had a dispute with the contractor a few weeks ago after several men had been injured, and planking was put up, averting a strike at that time.”

Severin Co., the construction firm overseeing the project, released a statement saying “every legal and extra-legal precaution had been taken to prevent rivets from falling” and that “the present planking complies with the regulations and has no cracks for rivets to fall through.” But they did fall and the injuries kept piling up, so Capelle took action.

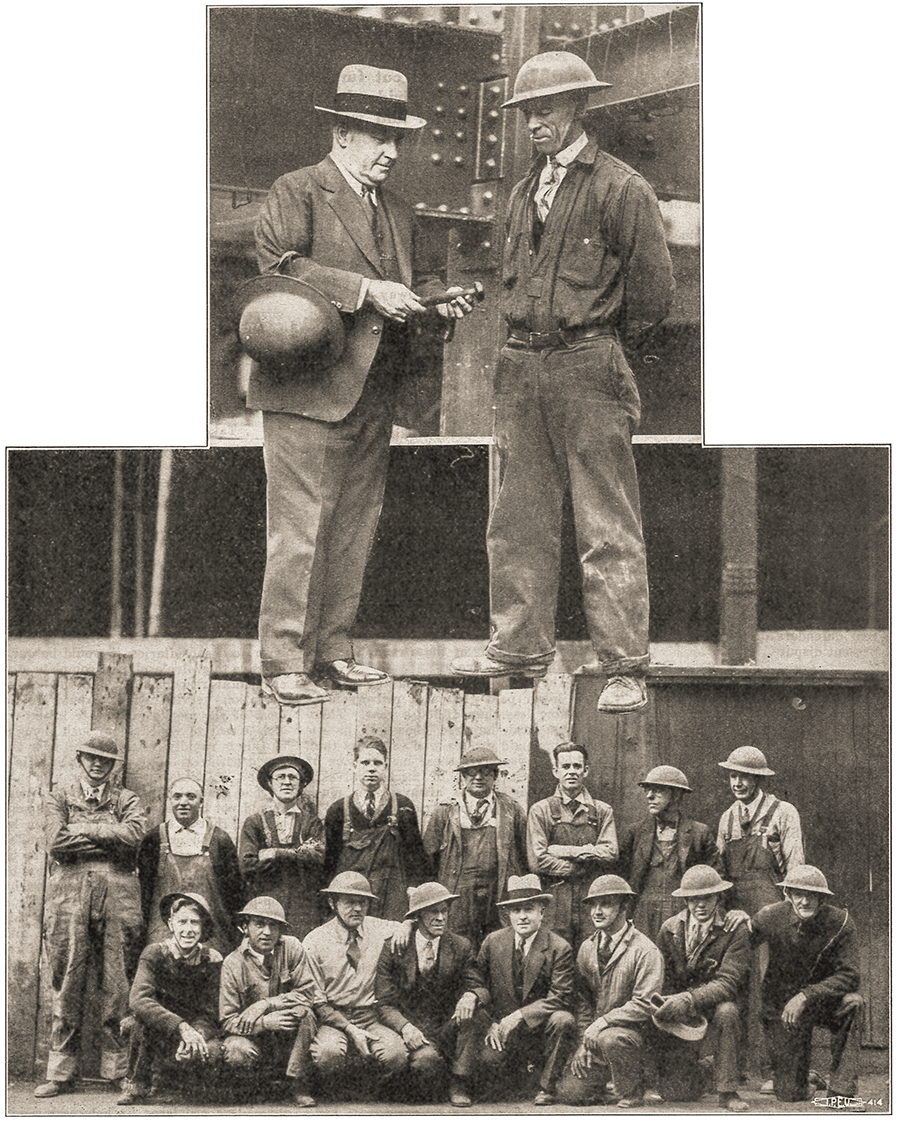

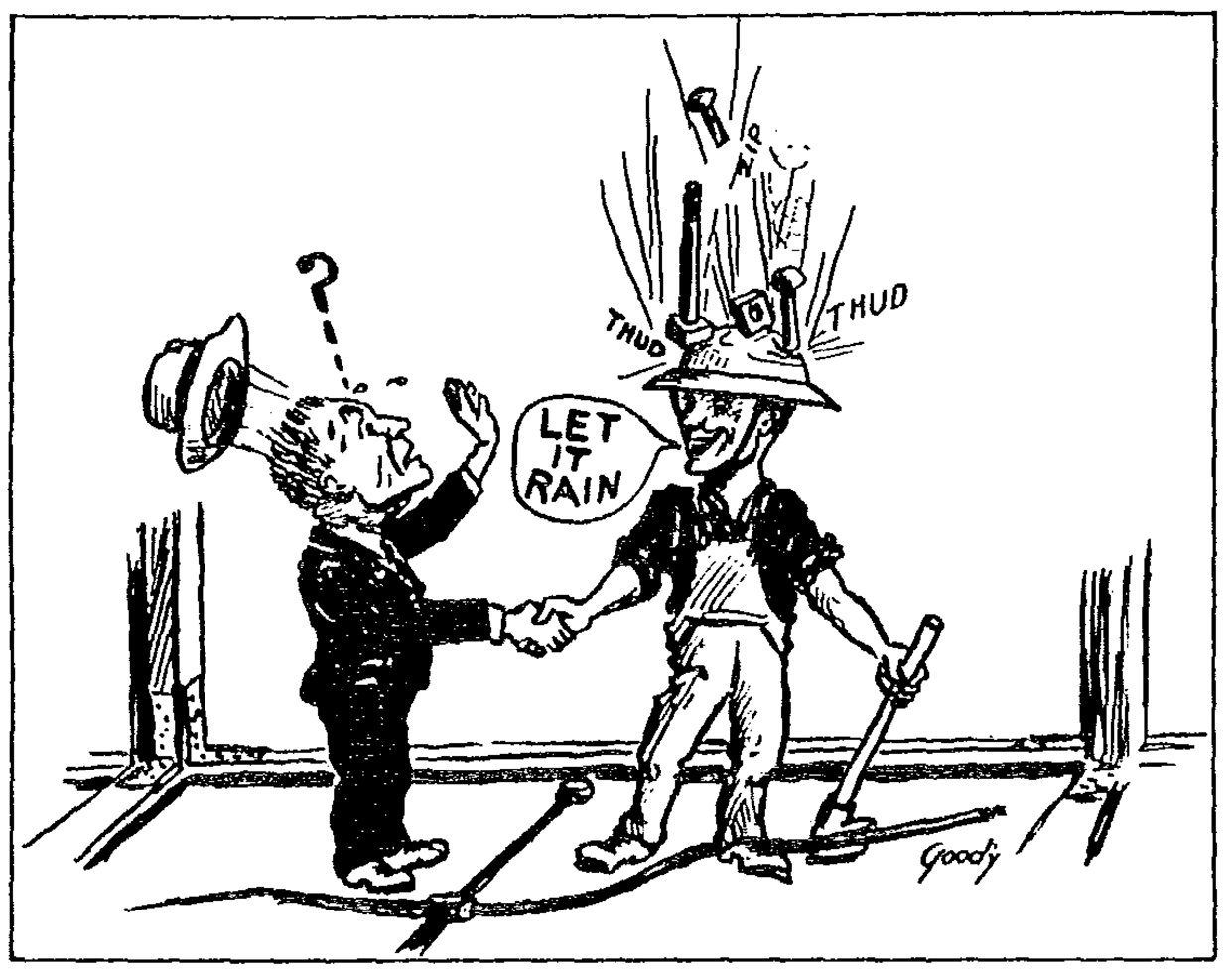

“Putting gray matter into operation, our energetic business agent visited a government storehouse and returned with a purchase of discarded army helmets,” Local 103 member Harrie Goodwin said. “He ordered his gang of electricians to go into action with precaution. It seemed humorous at first, but it is one of the cleverest safety measures that has been put into practice in this locality for some time.”

The sight of “Carnegie stetsons” or “tin derbies,” as the helmets were sometimes called, did cause quite a stir. The post office job was soon swarmed by photographers and reporters from Boston’s papers, resulting in front-page news.

“The doughboy who tucked away his iron derby when he got back from overseas has found a practical use for it,” reported The Boston Globe. “By order of Local No. 103, electricians at work on the post office will appear with iron hats as part of their equipment. If a member has no iron hat of his own, snared from the attic, dusted off and polished, he will be rationed a hat from the supply on hand at the government storehouse.”

Soon, the other crafts on the building followed Local 103’s lead, and the push for hardhats to become mandatory spread throughout the industry. “The contractor is not legally bound to obey the Massachusetts safety requirements,” Capelle said, “but he is morally bound to do so. If the ‘tin derbies’ fail to protect my men, we might find it necessary to call them off the job.”

In the end, the helmets worked and IBEW members were protected. The moral obligation to ensure worker protection, a founding principle of the IBEW, was once again the driving force that led to an industry standard.

Though unorthodox, it was the ingenuity of IBEW members that saw a solution where no one else thought to look. As Goodwin said: “Little did the boys think when bullets were plinking against the tin helmets in the trenches, that the day would come when they would be worn as backstops for rivets. But sometimes, that is how it comes about.”

Visit nbew-ibewmuseum.org for more on how to support the IBEW’s preservation of its history. Have a an idea for this feature? Send it to [email protected].