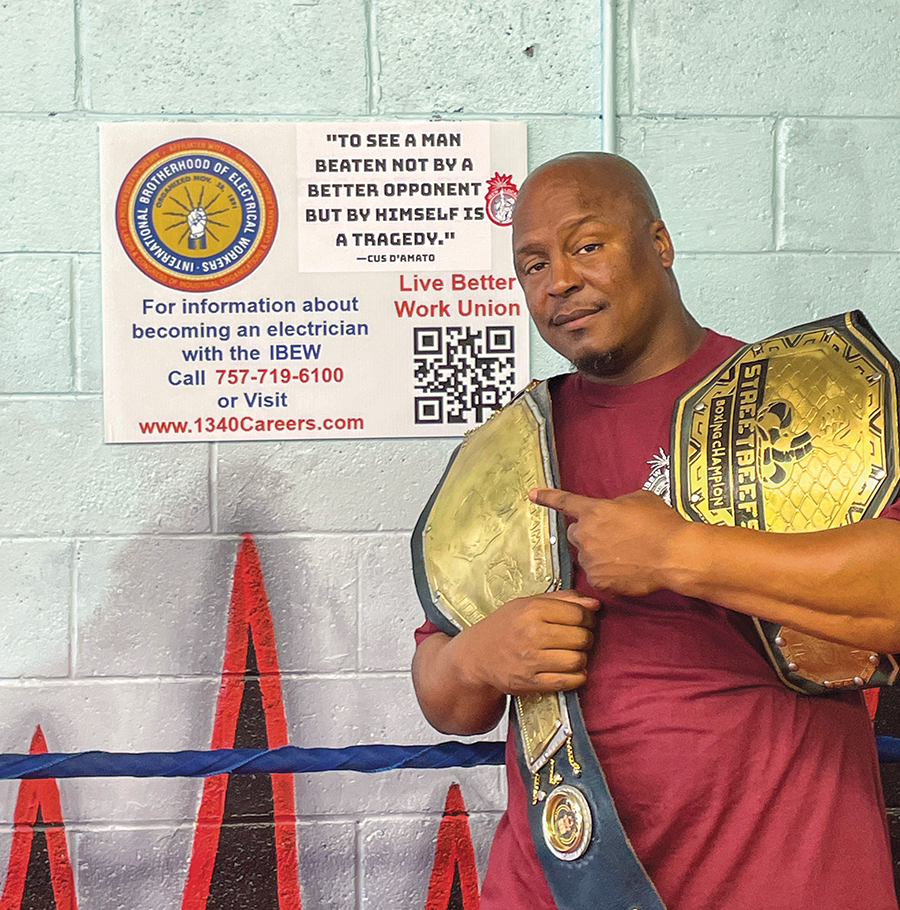

Members of the IBEW’s Fourth District often refer to themselves as “The Fighting Fourth.” Thanks to Newport News, Va., Local 1340 member Kenyon Johnson, they actually have a bona fide boxer among their ranks.

“Kenyon is a proud IBEW member who’s using the sweet science to better his community,” said Local 1340 President Aaron Woodard, referring to a term that describes boxing with an emphasis on the strategy and technique. “He’s even convinced me to get back in the ring and to try to get back to my fighting weight.”

Johnson learned about the IBEW from a member who lived up the street from his mother. Johnson was working in the residential sector but was nonunion. After some good-natured ribbing about a young Kenyon and his friends playing their music too loud, the neighbor, Joe Proctor, told him that if he wanted to make more money, and make a change, then the IBEW was the way to go.

“Joe took me down to the hall, I applied for the apprenticeship and started as a construction wireman,” Johnson said. “After that, it was history.”

Johnson quickly proved himself to be a hard worker who loves to learn everything there is to know about the trade. Still, he was apprehensive about starting the apprenticeship. It had been a long time since he was in school, and he was balancing working in security with raising a family.

“I’d never been in an organization like the IBEW. There’s no order to anything in nonunion work,” Johnson said. “It wasn’t easy, but all I had to do was take the time and put things in order.”

Johnson topped out in 2023 and makes a point of talking up the IBEW at every chance he gets, including before boxing matches.

“He’s always advocating for the IBEW and workers’ rights, and he’s always helping others,” Woodard said. “He’s a very active member and a great example of brotherhood.”

Woodard said it’s not unusual to get a call from someone that Johnson has met and who now wants to join the union.

“I love the IBEW. It feels good to have things like health care and benefits. This is grown man stuff,” he said. “I’m walking with my head held high.”

Johnson, a Louisiana native, started boxing around age 12. His mother was in the Army, so he learned on a military base from guys much older than him.

“I was the only kid,” he said. “The other guys were like my big brothers. They taught me to think past the pain, because after that is victory.”

Johnson, who competes as a heavyweight, went on to rack up a lot of victories, winning four belts.

“He’s got deceptively fast hands and good footwork for a guy with his build,” Woodard said. “He can stick and move like a welterweight and when he gets you tired, he’ll get inside and punish you with vicious hooks and uppercuts.”

Despite his skills and ambition, Johnson wasn’t immune from making the wrong move outside the ring. When he was about 19, he got caught up in a drug deal gone wrong and ended up in prison.

“Sometimes as boys, you try to find a lane, and you choose the wrong one,” he said of that period in his life.

Johnson used his time behind bars to take electrical courses, determined to never go back. Now he’s an advocate who regularly speaks at nonprofits and with Guns Down, Gloves Up, a movement to get teenagers to work out their differences through boxing instead of shooting.

“I don’t want to see others go down the path I did,” he said. “I’ve seen guys get killed for stepping on someone else’s shoes. This is a way to not throw your life away over some emotional situation.”

Johnson also gives back through the gym he opened, Pound 4 Pound Boxing Gym. He funds it himself and gives free boxing lessons to underprivileged youth as well mentorship and guidance. It’s also a place where fighters won’t be exploited, he said.

“I got tired of watching games at other gyms where promoters were lining their pockets. It was all about the money,” Johnson said. “This is a way to let me step in and show them a brotherhood, that this is the real way to fight.”

Johnson said he always makes sure to ask the kids who come in how their day was, aware that they might not be getting the best communication elsewhere.

“When they come in, I want them to feel at home, to know that I’ve got their back,” he said.

He also shows them his paystubs.

“I want them to know the truth. I want these kids to know about my path and the IBEW, and that they’re set as long as they stay in here,” he said. “I’ve saved myself, now it’s time to give back.”