When Sam Bossingham was growing up in South Dakota, he didn’t have any electricity. Little did he know that his path would take him to northern Michigan, where he co-founded an IBEW local, but not before fighting in World War II.

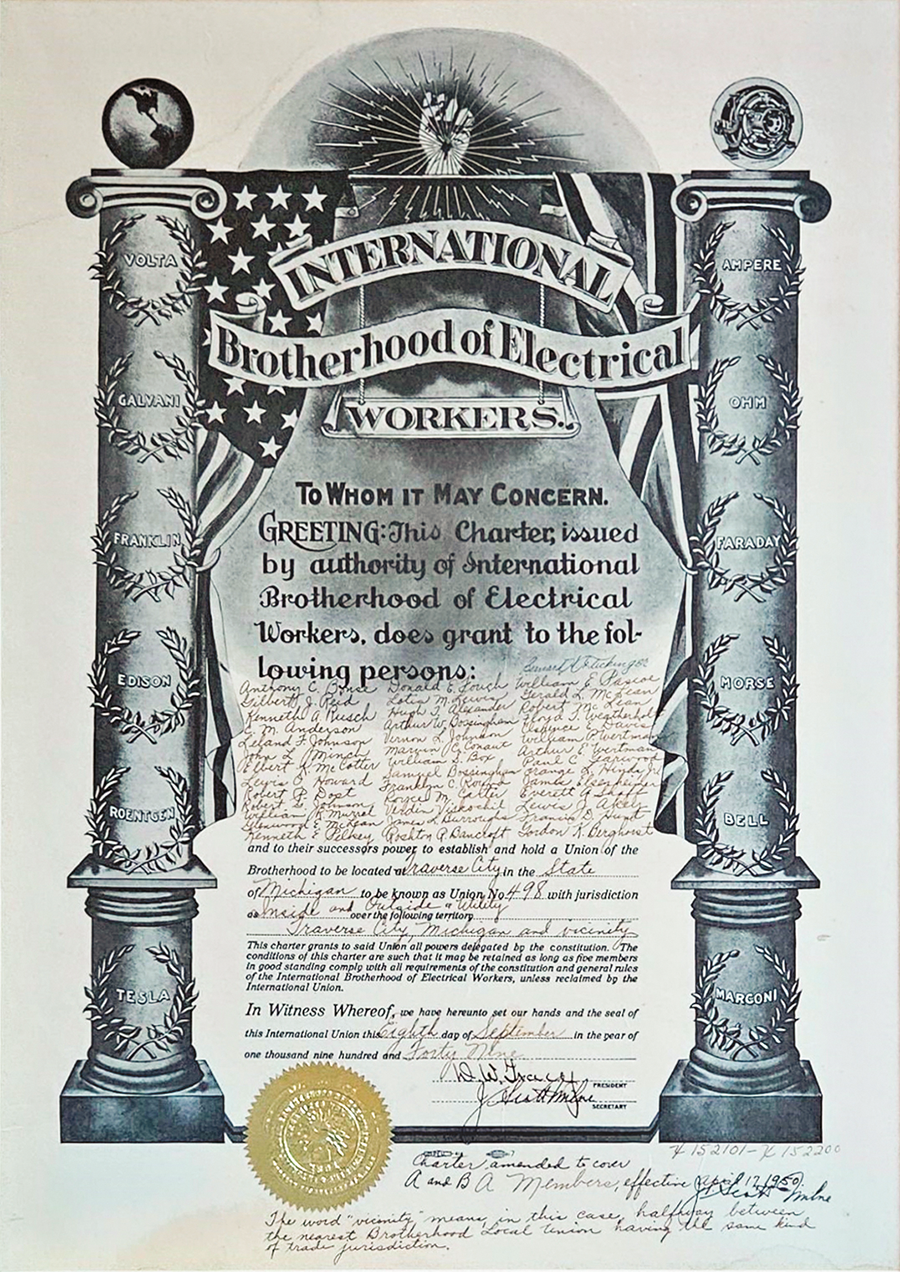

“I was proud to start Local 498,” Bossingham said of the Traverse City, Mich., local he helped found. “There’s nothing better than the union.”

Now 101 years old, Bossingham is the sole remaining founder of Local 498, which got its charter in 1949. He came to the trade after trying his hand at wheeling cement once he got home from the war.

But it wasn’t for him, so when he saw an ad in the local newspaper for a correspondence course in electrical work, he decided to give it a go. He studied hard and passed the exam on his first try.

“It came natural to me,” he said, noting that contractors would often call him for help. “When you do something you like, it makes you feel good.”

He worked nonunion in his early days as an electrician, until a couple of guys from Detroit Local 58 came to Traverse City and asked Bossingham about starting a local. Knowing what the union could offer, Bossingham and three other men, one of whom was his younger brother Art, set about starting a union.

“You couldn’t ask for a more stand-up guy to start the local,” Business Manager Dave Fashbaugh said. “Sam was one of those guys who put it in the textbooks.”

Fashbaugh added that Bossingham was one of the members who got the local’s pension started.

“He was very forward-thinking,” he said.

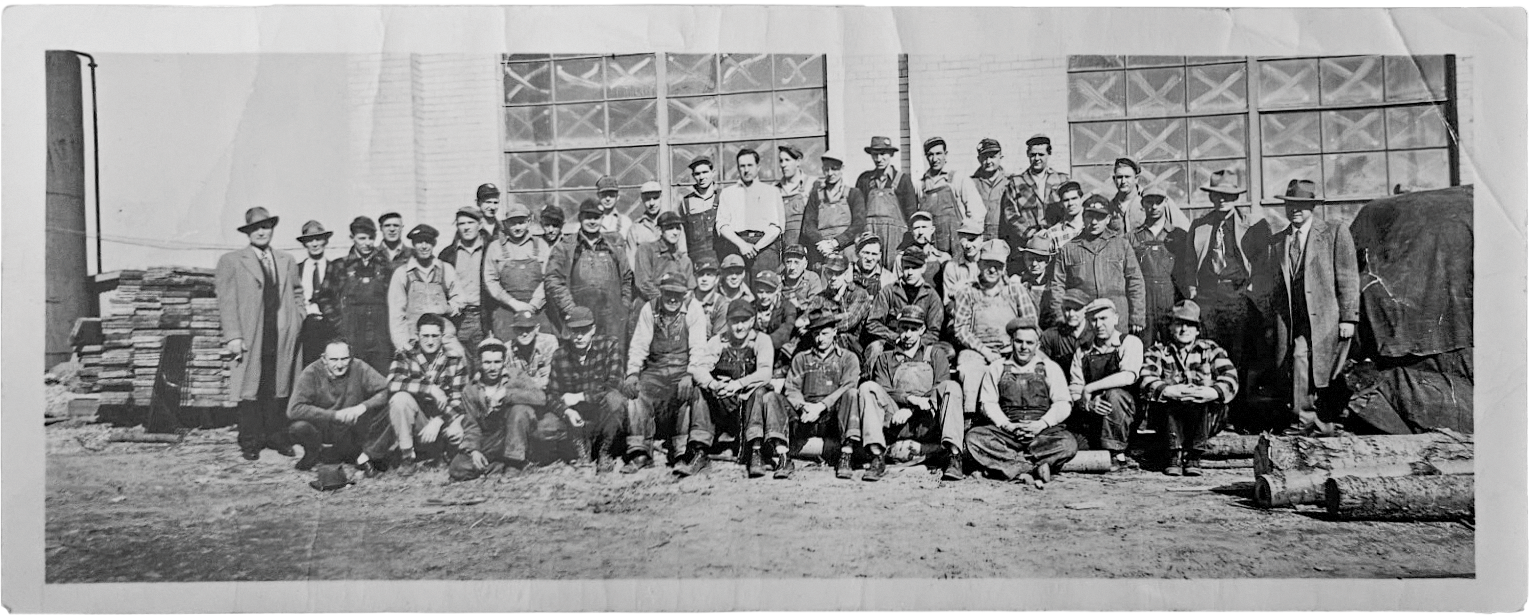

Bossingham and his soon-to-be brothers saw their chance to start recruiting at a big job at a paper mill in Manistee, about 65 miles southwest of Traverse City. It had about 50 electricians working on it.

“Most of the guys joined up,” Bossingham recalled. “They knew they’d get better wages that way.”

They also put ads in the papers in Charlevoix and Petoskey, about 60 miles north.

“For a while, we were paying for things out of our pocket,” Bossingham said of the early organizing days. But it paid off, and eventually they got their charter.

“We started a good thing. It makes me proud,” Bossingham said. “Working union was a lot better than before. And we were happy to get a low [local union] number.”

Working in electrical was a far cry from Bossingham’s childhood days on a ranch outside the Rosebud Reservation with no electricity.

“I was a cowboy in South Dakota,” Bossingham said. “I didn’t know how to put in a light bulb.”

The Great Depression and a series of natural disasters — drought, sandstorms, snowstorms and even a plague of grasshoppers — took their toll on the family cattle ranch. Bossingham’s father picked up and moved to northern Michigan, where he found work renting out horses for trail rides and other odd jobs at the camp that would later become the Interlochen Arts Camp.

In 1941, Bossingham moved to Michigan to help his father, but soon after signed up for the draft. Just two months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Bossingham was in basic training.

He was assigned to the 81st Chemical Battalion, and after a commanding officer made him a “buck sergeant,” the newly promoted Bossingham came to lead a team of 26 soldiers. Half of them did not make it home.

The most action they saw was in Belgium, where they were stationed for 120 days, Bossingham said, but the worst battle was at Omaha Beach in Normandy.

“They really slaughtered us,” he recalled.

More than 4,400 Allied soldiers lost their lives in that battle.

“The Army trained us to make ourselves as small as possible while taking fire,” Bossingham told the Record-Eagle, a local paper. “You forget about being scared and saving your life at those times. You do what you’ve been trained to do.”

Bossingham’s troops also endured heavy fighting in Saint-Lô in France.

“There was nothing left afterward,” he said. “The only thing standing was a church.”

Bossingham also saw combat at the Battle of the Bulge but was never injured during the war.

“I always figured that God helped me,” he said. “He always put me somewhere where I never got hurt.”

Bossingham’s brother Walter served, as well. He was captured by the Germans, but not before completing 21 bombing missions.

Bossingham said he would have been sent to Japan, but after the Americans dropped the atomic bombs, he was sent home. Walter made it home, too.

Like so many from his generation, he’s humble about all he endured, Fashbaugh said.

“I knew Sam was in World War II but not exactly what he did. To fight in the Battle of Bulge, Antwerp and Normandy and survive all three is unreal,” Fashbaugh said.

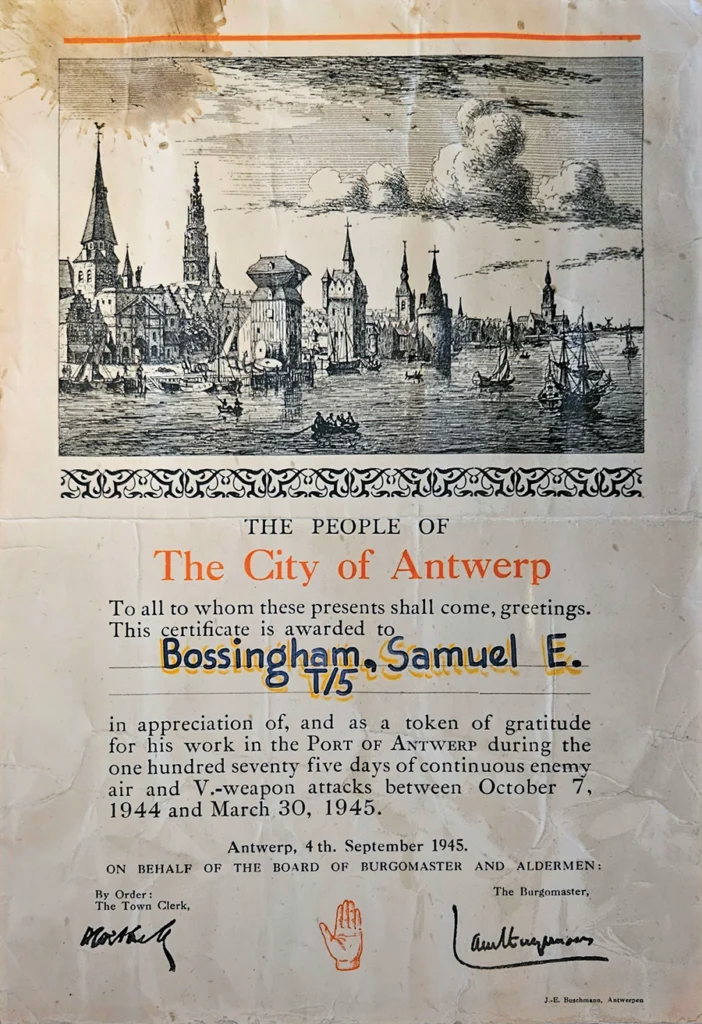

Bossingham does have accolades — a certificate of gratitude from the city of Antwerp, Belgium, and a hand-signed letter from President Joe Biden thanking him for his incredible service.

Bossingham just after enlisting in the Army. At right, the certificate of gratitude he received from the city of Antwerp, Belgium, for his heroism during World War II.

Bossingham retired in 1983 but has stayed active ever since. He kept his love of horses from his days breaking them in on the ranch, and didn’t stop riding until just three years ago.

“That’s a fun time,” he said of one of his favorite pastimes.

He still does calisthenics every morning, just like he was taught in boot camp, Fashbaugh said.

“He doesn’t look a day over 80,” Fashbaugh said. “He rarely uses his walker. He mostly just walks with a cane.”

Looking back on his life, Bossingham said he’s proud to have done his part and helped where he could.

“Not to brag, but I helped a lot of people,” he said. “I like to do that, though. It’s good for your heart.”