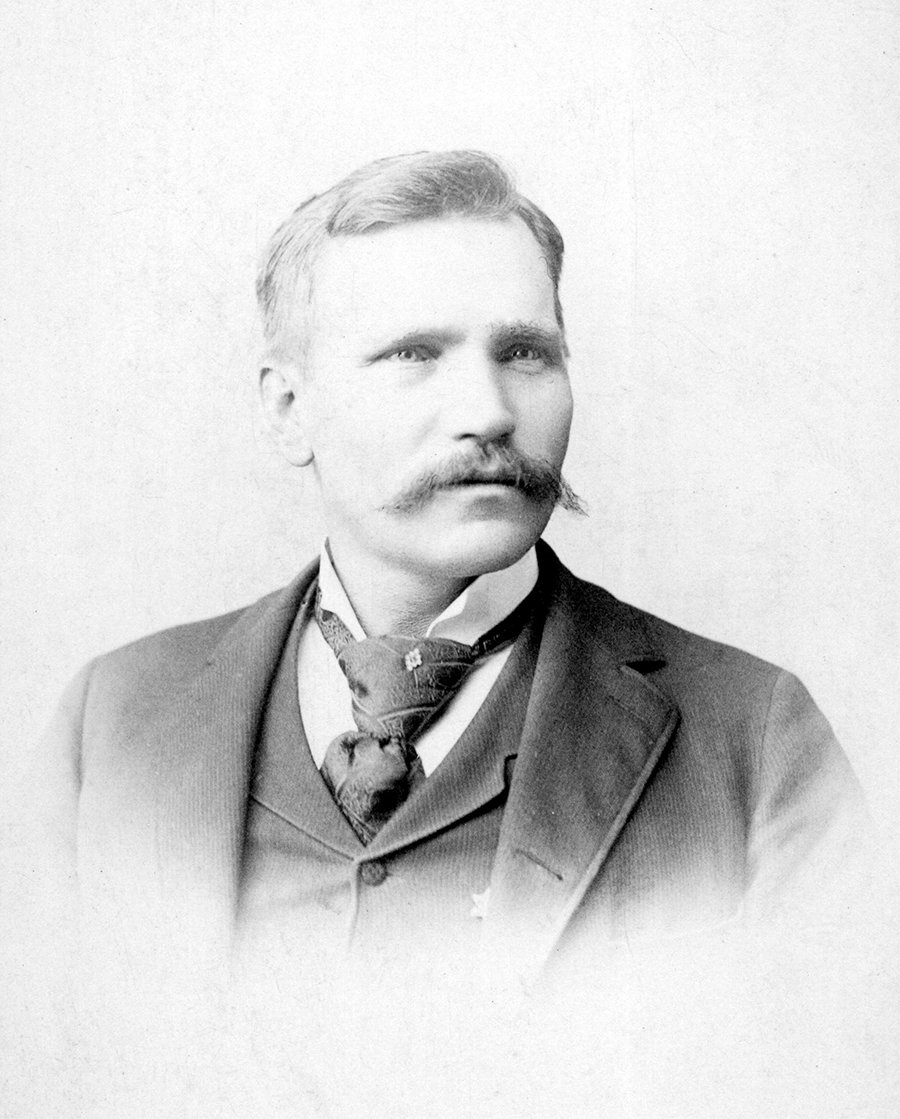

On July 11, 1896, Henry Miller, the IBEW’s founder and first president, succumbed to injuries he sustained the night before while on the job. He was called out to repair a downed line, but on reaching the top of the pole, he came into contact with a live wire and was thrown to the ground by 2,200 volts.

The inherent dangers to electrical work and the high rate of fatalities in the craft were the primary reasons he founded the IBEW in the first place.

He was buried in Glenwood Cemetery in Washington, where he remains today.

Word quickly spread, and letters of remembrance began flooding the office of Grand Secretary-Treasurer James T. Kelly. The first of these were published 129 years ago in the August 1896 issue of The Electrical Worker. Presented here are excerpts of a few, written by some of those who knew him best.

Edward Hart and L. Williams, Funeral Committee of St. Louis Local 1:

“Henry Miller, a charter member of Local Union No. 1, devoted his whole energy to the cause of organizing his fellow-craftsmen without compensation, and, though often in need, cold and hungry, never despaired about the future of the organization he so nobly sacrificed his time, health, and personal comfort to build up, and who, through all his hardships as well as triumphs, was as proud of Union No. 1 as a father is of his first child.”

James T. Kelly, grand secretary-treasurer:

“No man could have done more for our union in its first years than he did. … He was generous, unselfish, and devoted himself to the task of organizing the electrical workers with an energy that brooked no failure. Had there been more Henry Millers in our organization our progress would be greater in proportion to the number.”

James H. Maloney, grand president:

“In his rugged breast a manly, generous heart beat time to the best interest of his craft and his fellow man. His memory will be an incentive to others to add dignity to their calling, their chosen profession, by using their best endeavors and brightest attainments towards increasing the prestige of the NBEW.”

Daniel Ellsworth, member of Detroit Local 17 and a close friend of Miller:

“We well remember when he came to Detroit to organize us. He rode on the bumpers of a freight train to get here and had no funds for organizing. When we took up a collection for him at the close of the meeting, we fairly had to force him to take it. ‘No, boys,’ he said, ‘you will need all the money you can get together for your union. I will get along some way.’ I tell you, brothers, he was a hero in the cause, and as I think of him, I am reminded of a verse of Longfellow: ‘In the world’s broad field of battle/In the bivouac of life/Be not like dumb, driven cattle!/be a hero in the strife!’”

Henry Hatt, member of Local 26 and Miller’s roommate in Washington:

“I saw Henry Miller wire an iron smokestack, built by the Cramps of Philadelphia, 240 feet high, working on the outer edge on a narrow scaffolding. The sway of the iron by the wind was nearly three feet. Nearly every stormy night last winter he would have to go out on the circuit, as it was put up in trees, and had defective insulation. … He could do as much work in one day as two ordinary men and read novels half the night. In other words, he could do as much work in fun as some people do in earnest. … Peace be to his ashes.”

Today, Miller’s history is preserved at the IBEW Museum at the International Office in Washington, as well as the Henry Miller Museum in St. Louis, where he hosted the first Convention. But his legacy spreads far beyond those walls. It lives on in every member of the IBEW.

Visit nbew-ibewmuseum.org for more on how to support the IBEW’s preservation of its history. Have a an idea for this feature? Send it to [email protected].