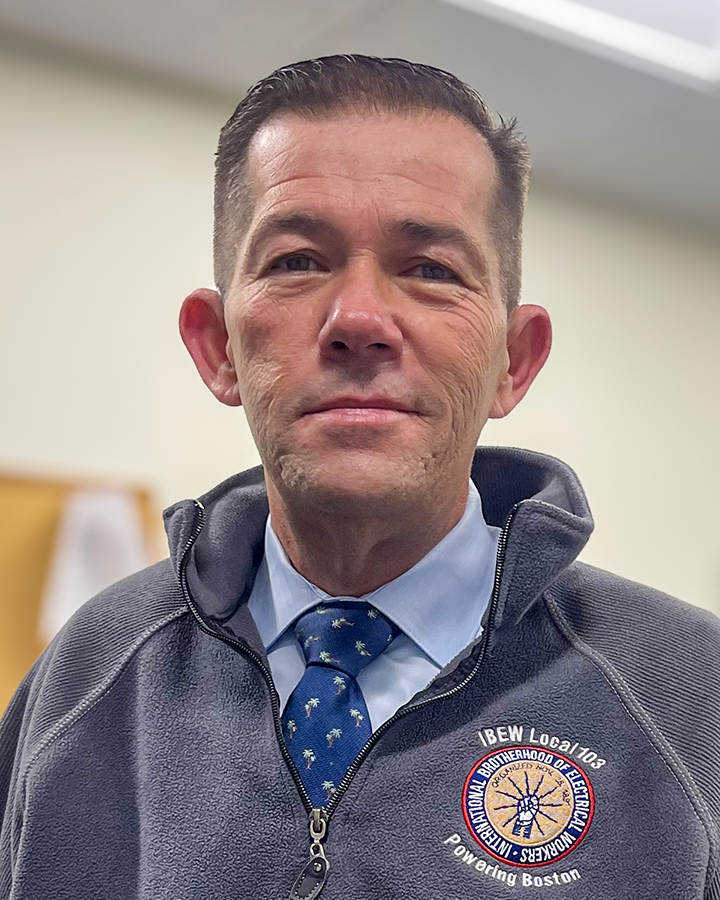

About a year and a half ago, Jay Frasier had a breakdown. In less than two weeks, his union, Boston Local 103, had lost three members.

One hanged himself, just hours after speaking with Frasier. About four days later, another overdosed intentionally. Frasier was on the phone with him and his mother when it happened, but they couldn’t get to him. The third death came when Frasier noticed that a member missed a meeting of the recovery and sobriety group he runs. They had taken a Percocet unknowingly laced with fentanyl, a drug more potent than heroin.

“I get attached to these kids,” Frasier said of the emotional toll it took on him. “It was a really hard time.”

The tipping point came when Frasier ended up on the floor of his kitchen, completely shaken and unable to pick up his phone to call for help.

“I lost my [expletive] completely. I didn’t understand what was going on with me,” he said. “It took me two hours to press the button. The phone felt like it weighed a thousand pounds.”

Frasier realized that he hadn’t slept or eaten in days. With help from his employee assistance plan, he eventually made it to a psychologist’s office. Still, he was worried that the receptionist was judging him.

“It’s about giving our members tools for living, and alternative ways to deal with stress.”

He’d managed to get off the floor, but not out of reach of the stigma of mental health treatment. But he stuck with it and got the help he needed. Now it’s a story he shares widely, as a way to show that construction workers, like everybody else, are not immune to emotional trauma.

“I think I went through that so I could do this,” the business agent said of his work running Local 103’s recovery and sobriety group. “The more we talk about it, the more we break the stigma.”

The group meetings are well attended, with close to 90 people showing up at a recent get-together. But Frasier makes a point to talk about addiction and recovery everywhere he goes, including at job sites during lunch and coffee breaks.

“It’s about giving our members tools for living, and alternative ways to deal with stress,” Frasier said. “It’s a scary time. People are on edge. If you don’t have a way to release, it builds up, and some people don’t have all the tools they need.”

Frasier isn’t afraid to think outside the box when it comes to helping members, as evidenced by a raffle the group did of an autographed Dropkick Murphys guitar, and another of a bottle of Jameson Irish whiskey, to raise funds for the group.

“We do crazy things,” Frasier said. “With the Jameson bottle, it was for the money, but we also wanted the conversation that would come out of doing it. Now more people know about us.”

In addition to creating an opportunity to spread the word about the group, the money goes to things like paying for stays at sober houses, a type of transitional housing that’s often crucial to getting someone through their recovery.

Frasier credits the members themselves for the group’s success, noting that they’ve already got common ground as Local 103 brothers and sisters.

“At Alcoholics Anonymous, you might be sitting next to anyone, maybe a doctor. With us, you already have a bond. We’re all carrying a dues receipt,” he said. “It automatically builds trust.”

Frasier said he ends every conversation with “I love you.” It’s a way to push back on the mentality that construction workers are tough and don’t talk about their feelings. It’s also a way to let others know they’re not alone.

“Nobody can do this alone,” said Frasier, who’s been sober for over 27 years. “If you’re struggling with anything, let’s get you where you need to be. You don’t have to do it all yourself. We’re all pulling in the same direction.”

Local 103 offers training in the use of Narcan, which can stop an overdose from becoming fatal. Frasier also encourages anyone who’s been injured and gets a prescription for pain medication to ask their doctor about how addictive it is and whether there’s something safer to use instead. And there’s the Family Medical Leave Act, which pays a worker close to their full wage for any time they need to take off work.

It’s all about saving members and giving them options, Frasier said.

“When you’re depressed or anxious, you feel like you don’t have anywhere to go,” he said. “All you know is that you want to feel better.”

For Frasier, a big part of that is the union solidarity that comes from having each other’s backs.

“You can spend more time with your tool partner than your spouse,” he said. “If you notice that someone is acting different, if they’re off their baseline, get their partner to talk to them. At the end of the day, the biggest tool we have is each other.”