“What does it profit a man to be able to eat at an integrated lunch counter if he doesn’t earn enough money to buy a hamburger and a cup of coffee?”

– Martin Luther King Jr., March 1968

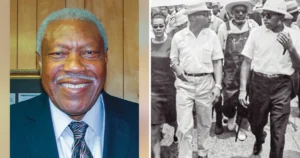

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., seen here at the Lincoln Memorial during his “I Have a Dream” speech in 1963, made clear that labor rights were central to the Civil Rights Movement.

Charlie Horhn’s activism took root in a segregated factory in Jackson, Miss., where “Colored” signs hung over the cafeteria, water fountains and restrooms Black workers were allowed to use. Even work areas were separated. Away from the plant’s whites-only assembly line, Horhn and other Black men forged components of small kitchen appliances for meager wages and the occasional nickel-an-hour raise.

He’d arrived at Presto Manufacturing in 1955, the same year that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s roaring calls for civil rights were first recorded, sermons that became entwined with labor rights. Until the day he died in April 1968, assassinated after marching with striking sanitation workers in Memphis, Tenn., King preached that economic and workplace justice were essential to achieving true freedom and quality.

Horhn, now 91, embodied King’s message. He marched for civil rights and doggedly registered Black voters, sharpening the organizing skills that would help persuade a majority of his 700 co-workers, Black and white alike, to join the IBEW.

“The labor movement saw how it could grow through the Civil Rights Movement, and the Civil Rights Movement saw how it could grow through labor,” Horhn said.

He remembers well the hard-won campaign that created Jackson Local 2268: An election loss in 1966, a victory in 1967 and three years of company appeals all the way to the Supreme Court. Three tenuous years holding workers together under the IBEW banner until they finally sat down at the bargaining table in spring 1970.

“It was a new day,” Horhn said. Within two months, Presto workers had a first contract with a 30-cent hourly raise; additional vacation days; and provisions on seniority, grievances, absences and more.

For Horhn, there would be many more triumphs ahead. The man who grew up on a farm in the Jim Crow South, who paid a $2 poll tax to vote while white precinct workers mocked him, would rise to be a powerful agent of change on the battlefields of labor, civil rights and politics.

He started with Presto. Appointed chief organizer of the new union, he used his clout to advance a longtime goal: more and better opportunities for Black women, who were restricted to the plant’s kitchen and daycare. Meanwhile, white women had jobs on the factory floor, some even joining men on the assembly line. “The company claimed Black women couldn’t pass the aptitude test,” Horhn said with disgust.

The 1964 Civil Rights Act made workplace discrimination illegal, but little had changed at Presto. Enforcement was lax. “Colored” and “Whites Only” signs came down, but a culture of segregation remained. Black men finally got tired of waiting. “We’d decided we were going to start integrating the bathrooms, water fountains and cafeteria ourselves,” Horhn said. “One night on the midnight shift, a group of Black employees walked into a ‘white’ restroom. A group of white men chased them out with pipes.”

No one was hurt. But tensions rose the next day when white workers marched out of the plant en masse in support of the racist mob. Trying to cool hostilities, the company formed a biracial committee, appointing Horhn and a white man as co-chairs. At the same time, Horhn was quietly engaged in another attempt at unity, the nascent organizing drive.

Horhn was proud of his sterling record at Presto, popular among his co-workers and respected by managers. As fervently as he would fight for the union, fear of losing his job kept him in the shadows at first. He found his courage when an IBEW international organizer explained that he was better protected out in the open. Otherwise, the company could fire him on phony grounds and lie about knowing he was a union supporter.

“The man said: ‘Monday we’re going to handbill the plant. I want you out there on the front line,’” Horhn recounted. “So I stood out there and handed out literature. Some of my co-workers thought I was crazy. They didn’t want to come close.” Spotting him, the plant manager later dispatched an assistant, Elmer, to ask Horhn what he wanted. He didn’t mince words: “You tell him the greatest thing I want is a union.”

Horhn wasn’t finished. “I told Elmer that I’d continue to be a good employee,” he said. “That was my record and I planned to keep it, but he could tell Mr. Halle that on my break times I’ll be talking to employees about the union.”

After the first election failed by three votes in 1966, organizers doubled down on their resolve. A year later, they won by a sizable margin, due in no small part to the Black women who’d been hired as a result of Horhn’s efforts. For the next three years, union leaders hustled to keep the coalition united against company’s attacks as Presto’s fight to derail the victory played out in court.

With the union certified and contract achieved, Horhn’s influence in the labor movement grew steadily. Between 1972 and 1974, he established Mississippi’s first chapter of the A. Philip Randolph Institute advancing Black trade unionism and activism, became a founding member of the IBEW’s Electrical Worker Minority Caucus, and began 20 years of service as Local 2268’s president and business manager.

Understanding how politics and politicians could harm or help his members, and all workers and minorities, Horhn threw himself into campaigns for Black and pro-union candidates. His many successes include his eldest child, John Horhn, who served 32 years in the Mississippi Senate before being elected mayor of Jackson in 2025.

Politics became Horhn’s full-time career in 1993 after he ran the campaign that sent Bennie Thompson to Congress and was appointed as his district director. Now in his 17th term, Thompson was only the second Black lawmaker elected to represent Mississippi since Reconstruction.

For 20 years, Horhn oversaw constituent services and other district business in 23 counties, retiring in 2014 at age 80. The outpouring of gratitude and affection included a joint resolution in the Mississippi Legislature that saluted his “20 years of achievement and enormous civic energy,” and noted that the U.S. House “recognized Charlie as one of America’s most dedicated public servants.”

A widower, Horhn still lives in Jackson, with family there and across the South. “Five children, seven grandchildren, eight great-grandchildren and two great-greats,” he said.

Speaking with The Electrical Worker, Horhn brought his story full circle, remembering the choice he made as he and other early supporters contemplated an organizing drive at Presto.

“I’d been contacted by IUE (furniture workers) and the IBEW,” he said. “When I weighed the strength of the two unions, I found the IBEW was the strongest one for our workers and the products we made.”

He’s proud of his lifetime of service but stressed more than once that he doesn’t like “to toot my own horn,” giving credit instead to the forces that shaped him, including the IBEW.

“I was a boy from a country farm,” Horhn said. “The union, they got me to be the man that I am. The union and the Civil Rights Movement.”