May 2024 |

|

|

|

|

Print Print

Email EmailGo to www.ibew.org |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

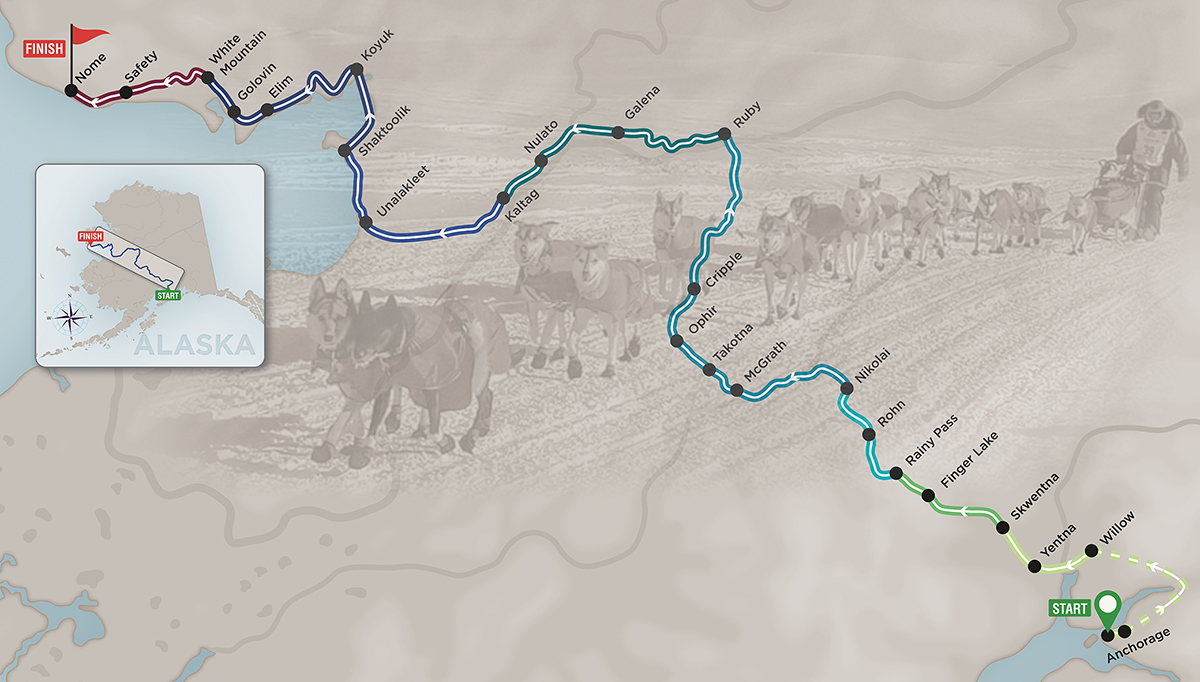

When Wally Robinson saw a dog sled team in full flight for the first time, he was 14. No moment except his marriage and the birth of his children charted the direction of his life more than standing next to his father, Walter, on the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, mouth open and eyes opened. Walter, an inside wireman at Marquette, Mich., Local 906, brought Robinson to the race because he'd helped light it. A tragedy the year before left a racer dead after he strayed far off course on a frozen lake. The contractor where Walter worked stepped up to pay some journeymen to make the trail more visible. Robinson was just tagging along with his father, who wanted to see what he had built in use. It was also a good excuse for some ice fishing. Make a day of it. Robinson made a life of it. The connection between the people on the sleds and the graceful, strong, determined animals was like nothing he had ever seen before. He read everything he could about mushing, and soon he was tying up the family coonhounds to some cheap plastic sleds. He ground through the bottoms of three sleds that winter. That's when the Upper Peninsula started feeling too far south. "As soon as I could, I knew I was going to Alaska," Robinson said. As soon as he could was after high school in 1999. A quarter-century from that day, the Anchorage, Alaska, Local 1547 inside wireman ran his second Iditarod, the longest dog sled race in the world. With nearly 1,000 miles of snow, mountains, ice and tundra, the Iditarod is the only dog sled race most people outside Alaska have heard of. Just a month and a half before he stood at the start, he had no idea he was going to be there. In late January, Josh McNeal, a friend and neighbor, tore a muscle in his shoulder more than a year into his training. Would Robinson want to step in? The kid who mushed coonhounds and moved 4,000 miles to race was still inside the journeyman. But it had been 23 years since he last ran the Iditarod, back before family, before starting in the trade. Robinson has been a familiar presence at many races since, but most of the time he was there as coach, chauffeur and dog handler for his kids, Emily and Stanley, both exceptional mushers. For more than a decade, Robinson was the inside business representative in the Fairbanks office of Local 1547, a more-than-fulltime job. But two years ago, he left the office and went back to the tools, and he has had more time with his family, more time in the backcountry and more time with his kennel of 30 racing dogs. He knew his trade, and he'd given back a great deal to the union that made this life possible. So he said yes. And then he did something extraordinary. He didn't just show up. He didn't just finish. He nearly broke into the top 10 and beat his old time by more than three days. And proudly sewn on his sled was the IBEW bug with its fist and lighting bolts. "I say all the time, our dog team runs on union power," he said. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

Coming to Alaska |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

Robinson comes from an IBEW family. His grandfather George was the first, a member of Coopersville, Mich., Local 275. Walter was president of Local 906, and uncles George II and Ben were business managers of Local 275. The IBEW is also home to a handful of his cousins. But Robinson didn't join the IBEW when he first came to Alaska in 1999. He went for his dream and lived it. "It's an apprenticeship being a handler, and I spent two years learning at a pro Iditarod kennel," he said. The kennel raised Alaskan huskies, the world's greatest sled dogs. The best of them can run 100 miles a day at about 12 miles per hour, day after day, thriving between 15 degrees above and 20 below. In 2001, Robinson got a shot to run the Iditarod with yearlings, younger dogs running the long race for the first time. These were dogs he knew from when they were born. The goal isn't to challenge for the podium, it's to find the dogs who one day will. "With young dogs, you run a much more conservative race," he said. Some of his major sponsors and supporters were the locals back home in Michigan. "I had [an IBEW] bug on my sled all the way to Nome," he said. But even for the most successful mushers, life in Alaska is too expensive to survive on winnings alone. In 2002, he applied for and was accepted into the Local 1547 apprenticeship. He topped out in 2007 and went to work. He married Alissa and became a father, first to Emily and then Stanley. Soon, Robinson was asked to come into the office. "The dream was to be a professional musher, but you need a career to support you," he said. "My dad and uncles taught me you give back to the local. I am grateful I did and learned a lot." And Robinson was all in, said Ninth District International Vice President Dave Reaves, former business manager of Local 1547 and Robinson's boss. "He jumped in feet first in the office, but also the evenings, the weekends, the labor walks, helping candidates get elected in every office at every level in Fairbanks," Reaves said. "The Fairbanks office made a huge difference for working people, getting allies elected, changing policies, getting PLAs on major projects." But Reaves knew it came at a very high price. "Having to do that pulled him away from the outside activities he came to Alaska to do. It pulled him away from his family, as much as he involved them in the work," he said. "He understood what giving back to the union is. He was raised to know it, and every IBEW member in Alaska benefited from his work." |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

Back to the Iditarod |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

About four years ago, Robinson daughter, Emily, got into racing, and he moved back into that world, but as a coach and trainer. "We have sled dogs, but I backed off racing," he said. Until this year. At the end of January, about a month before the Iditarod start date, McNeal was injured during the Kuskokwim 300 race. "I just happened to hit a tussock right as we were cruising along, and just kind of jerked my shoulder," he told the Alaska Daily News. "The next thing I knew, I couldn't lift up my arm." By the beginning of February, a few weeks before the start, it was clear that racing was impossible. He called Robinson and asked if he wanted to take the reins. "He said, 'It would be a bummer for the dogs to just sit around,'" Robinson said. Robinson had time off from his job on the maintenance team at Clear Space Force Station. But he was closer to 50 than 40, and it had been nearly a quarter-century since he ran the race. It was no light decision to make. The word "sled" probably isn't very helpful if you want to picture what a musher does during a race like the Iditarod. Instead of riding a sled, picture the Iditarod as running nine marathons in about 10 days, on snow and in wind chills that frequently drop below minus 40 degrees Fahrenheit. "It's hard to put a number on it, but I'd guess 20% to 25% of the time we are running," he said. "We are helping." When you aren't running, you're kicking the sled along like a skateboard or pushing with ski poles. "You time your runs to maximize the benefit to the dogs," he said. The dogs get maximum benefit when they don't have to pull the musher uphill. When the trail is running uphill, you are running uphill. To get in this kind of physical condition takes more than a few weeks. Robinson ran a half marathon in the fall of 2023 and liked it so much that he signed up for a 50-kilometer ultra-marathon in Arizona. He parked a treadmill in the entryway to the family sauna and had been training for months. But being fit is the beginning. The Iditarod throws you tests no treadmill can prepare you for: wildlife, cold, isolation, injury. But the greatest challenge could be exhaustion. There are only three required rests during the race. Somewhere, anywhere, there is a full 24-hour stop. Somewhere along the 150 miles of the Yukon River, you have to take the first eight-hour break. The only compulsory eight-hour rest is at the White Mountain checkpoint, 77 miles from the finish. Every other rest is optional, taking time off when other racers are moving. Robinson said that ideally, he sticks to a 10-hour cycle: six hours of running — "snacking" the dogs twice along the trail — and four hours of rest. But even rest from the race is grueling. "It's a break from the trail, not from work," Robinson said. The dogs are unhooked. Straw is laid out for them to lie on. They curl up, tails protecting their noses and feet, and sleep. "I send out massage oil to the checkpoints for their feet. I go through wrists and shoulders. Then I organize all the gear. Set up snacks for the trail," Robinson said. The musher boils enough water to defrost the dog food — a mix of salmon, beaver and moose meat. Gloves come off to remove the booties; every dog wears a set of four, each custom fitted. They come off at the start of the break, and new ones go on before they leave. No matter the weather, they are all taken off and put back on bare-handed. Only after the dogs are cared for does the musher get some food. "I have a bunch of vacuum-sealed bags of moose lasagna and moose spaghetti," Robinson said. "On a four-hour rest, I am lucky to get 45 to 60 minutes of sleep," he said. "The rest is taking care of the dogs." The last challenge is the money. Running the Iditarod costs about $20,000, and unless you finish way up in the standings, you don't fund it with prize money. Clothing is technical, durable and expensive. Sleds are handmade, and some racers bring two, with a lighter one for the final stretch along the coast where the snow is wetter. Booties can't be reused, and at $2 each, a team of 16 dogs uses $1,000 in booties. And then there's the food. Robinson said he spends $25,000 a year on his kennel just for food. "The cost is kind of ridiculous," he said. But with each of these challenges, Robinson could say yes. His journeyman ticket gave him the money and the safety net of retirement and health coverage that keep his Iditarod dream alive. And just like in 2001, he was supported by his brothers and sisters in the IBEW and across the wider labor community. Again, he carried the IBEW bug on his sled. Local 1547 came through with welcome resources, as did a Teamsters local back in Michigan, Alaska Laborers Local 942 and the Fairbanks Central Labor Council. They remembered all the years of work he'd done for labor in Alaska, and they showed up for him. "Alissa sewed it on. We also had the bug on the trucks and campers. It means a lot to me," he said.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Robinsons Are Not Done |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

When he left the starting line, Robinson had a mixed crew. He brought three of his own dogs — Urchin, Vickie and Lake — he knew and could rely on, with the other 13 McNeal's dogs. "My goal was to finish 20th," he said. This was a reasonable expectation, better than any substitute named so late had ever done. It turned out to be far too modest. He finished in 11th place in nine days, 23 hours and 22 minutes, a time that would have won the race between 1973 and 1994. If he had finished this fast in first race in 2001, he would have placed second. He also won the award for most improved and the Leonard Seppala Humanitarian Award, given to the musher who ended the race with the healthiest pack of dogs, according to race veterinarians. This award is about respect for craft, honoring your dogs and protecting your pack. This is an award a union lifer can feel in their bones. No job is a good job unless everyone comes home the same as they left. "When I look at that, I am super proud," he said. "To finish 11th is frickin' awesome. No one expected it, especially me. But when I start thinking … I am super competitive. I definitely screwed up, and the screw-ups were my fault." But for a competitor like Robinson, it was awfully hard to look at the five-hour gap to a top 10 finish or 15 hours to get into the top three and wonder about what he could have done better, including getting only a few hours of sleep on his 24-hour break. By the time he got to Unalakleet, he said, he was a wreck. He was in eighth place. He allowed himself a short rest at the checkpoint, but all the bedrooms were taken. Another musher, Pete Kaiser, had one of the bedrooms but let Robinson in as long as Kaiser could keep charging his phone. Robinson's phone was almost dead, but he set an alarm and told himself, "Even if the phone dies, I'll stay no later than Pete coming in to unplug his phone in half an hour." He woke up six hours later, in 11th place. The Seppala Award came with a prize: free entry into another running of the Iditarod, an open invitation to run it again. He's young enough to do it. He has experience to build on. Is he already thinking about next year? No. The youngest you can run the Iditarod is 18, and his 16-year-old daughter, Emily, is a phenom in junior mushing. She's won the Junior Iditarod all three years she's run it. If she wins next year, she'll be the first win all four years a junior musher is eligible to run. This year, she was one of only two juniors invited to run the Knik 200. The other 40 teams were mushing veterans, including two past Iditarod champions. Emily Robinson beat them all. "It's kind of a big deal," her father said. Eleven-year-0ld Stanley, meanwhile, placed second in the Willow Jr. 100-miler. He lost by 12 minutes. To Emily. A woman hasn't won the Iditarod since Susan Butcher won it for a fourth time in 1990. "You'll see a Robinson again," he said. "It just probably won't be me." |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

© Copyright 2024 International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers | User

Agreement and Privacy Policy |

Rights and Permissions |